2. Introduction

Background

The Sentencing Council (‘the Council’) was established to promote greater transparency and consistency in sentencing, while maintaining the independence of the judiciary. One of the primary responsibilities of the Council is to develop sentencing guidelines and monitor their use. The Sentencing Code states that courts must follow any relevant sentencing guidelines, unless it is contrary to the interests of justice to do so.

Since September 2015, sentencing guidelines for use in the magistrates’ courts have been published digitally on the Council’s website. Guidelines for the Crown Court were digitised in November 2018. Prior to this, guidelines for use in both the magistrates’ court and Crown Court were published and distributed in hard copy to sentencers.

In November 2021, the Council published its strategic objectives 2021-2026 in response to a public consultation about its future strategic aims and priorities. In these objectives the Council committed to “commissioning work on user testing of guidelines…the aim of the project is to test how sentencers use, access and experience digital sentencing guidelines” (pg. 45). Prior to 2022, the Council had not undertaken any formal research projects exploring the usability of the guidelines, following the transition to delivering the guidelines digitally.

To meet this commitment and better understand how sentencers use and experience the guidelines online, the Council conducted a survey of sentencers in 2022 to obtain quantitative information (as well as some qualitative feedback) on sentencers’ use and experience of the digital guidelines. It then commissioned the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) to undertake a qualitative user testing research project with sentencers that was informed by, and complemented, the earlier research.

Objectives

The objectives of this research were to:

- provide the Council with a better understanding of how sentencers engage with the sentencing guidelines on the Council’s website

- provide recommendations of aspects where the user experience of the guidelines could be improved

In meeting these objectives, this project explored the following research questions, related to the usability and experience of the guidelines:

- searching for guidelines: how easy is it for sentencers to use the guidelines with the current search functionality?

- using the guidelines: how easy is it for sentencers to use the guidelines given the current layout and format of the guidelines?

- navigating the guidelines: how easy is it for sentencers to navigate to different guidelines and additional sentencing resources, on the Council’s website?

- accessing the guidelines: how do sentencers find and access the guidelines?

- sentencing with the guidelines: how do sentencers use the guidelines when making sentencing decisions?

Scope

This research project focused specifically on the sentencing guidelines listed on the Council’s website for the magistrates’ court and Crown Court (‘the guidelines’), rather than any other part of the website. It focused on the usability of the guidelines specifically as accessed via a laptop, which the survey conducted in phase 1 indicated was the most common device used.

While sentencers may access the guidelines via phones, iPads or other devices, the usability of the guidelines on such devices was excluded from this project. Similarly, while the guidelines are also available via an app for use on iPads, this was also outside the scope of this research project.

Additionally, this project focused on the offence specific and overarching guidelines and did not undertake specific user testing of the digital tools available within the guidelines (e.g. the fines calculator, pronouncement builder, Sentencing ACE tool, etc.)

Nonetheless, where feedback was provided to researchers on topics outside the scope of this project, this report has sought to include such comments where appropriate.

3. Methodology

Overview

To answer the research questions for this project, BIT researchers undertook three research activities:

- In-person observations

Researchers observed nine magistrates (formed in groups of three to reflect the fact that magistrates’ ‘benches’ are typically comprised of three magistrates) in-person, while they were making sentencing decisions using paper-based mock scenarios. - Virtual usability testing

Researchers observed 17 sentencers (nine magistrates, eight judges) interacting with the digital guidelines whilst undertaking mock sentencing exercises online, and completing tasks related to using the guidelines. Sentencers shared their screen with researchers to demonstrate their interaction with the guidelines during these sessions. - Semi-structured interviews

Researchers interviewed 13 sentencers (10 magistrates, three judges) to gain feedback on their experiences with the guidelines. This included what works well and what could be improved about the guidelines to better meet the needs of sentencers.

Overall, a sample of 35 unique sentencers were involved across these three research activities. This included 26 magistrates, seven circuit judges, one district judge and one deputy district judge. There were four interview participants who were involved in both virtual usability testing sessions and interviews (two magistrates, one deputy district judge and one circuit judge).

Researchers carried out virtual usability testing and in-person observation sessions across December 2022 and January 2023, with interviews held in January 2023. With participants’ consent, virtual usability testing and interview sessions were video and audio-recorded, with automatically-generated transcriptions gathered for each of these sessions. In-person observations were also audio-recorded, with participants’ consent. Further details on these activities are provided below.

In addition to these research activities, this research project also undertook a high-level review of the layout of the guidelines, based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) principles. The WCAG provide guidance on how information should be published online, to be more easily accessible to people with different levels of ability. This includes differing levels of visual, hearing, physical and learning ability. Improving the accessibility of the sentencing guidelines will help make the guidelines more inclusive by providing people with equal access to this information. The WCAG also informs the UK government’s accessibility requirements for digital content.

The results of a survey of sentencers conducted by the Council about the guidelines were also reviewed by researchers. Responses were collected between September and October 2022 (see the report ‘User testing survey analysis – how do guideline users use and interact with the Sentencing Council’s website? Part 1’).

Participants

Recruitment

Researchers worked with the Council to invite sentencers via email to participate in research activities. Magistrates and judges were recruited using a purposive sampling approach in order to understand their experience of engaging with the guidelines.

For virtual usability testing and interview sessions, the Council sent an email to sentencers outlining these two research activities, which contained a link for them to register their interest in participating in these research activities. Sentencers were informed their participation was entirely voluntary and that no personally identifiable information would be provided to the Council. Within the online registration form, sentencers were asked to indicate their consent to being contacted by BIT and to complete a brief online questionnaire in advance of the session to provide the following information:

- age range

- gender

- judicial role

- confidence in digital literacy

- overall experience of using the guidelines

This information was requested in order to recruit a purposive sample of sentencers with a range of different experiences and circumstances and to help understand how the guidelines support sentencers with a spread of different experiences.

To measure confidence in digital literacy, participants self-reported their confidence on a 5-point Likert-type scale (with 1 being ‘not at all confident’, and 5 being ‘extremely confident’). Similarly, participants self-rated their experience of the guidelines on a 5-point Likert-type scale (with 1 being ‘very poor’, and 5 being ‘very good’).

For in-person observation sessions the Council provided BIT with contact details of two London based magistrates’ courts interested in facilitating in-person observation sessions.

Participants who registered their interest in the study were provided with an information sheet from BIT which reiterated that participation in these research activities was entirely voluntary and that they would be able to withdraw from the research at any point. Prior to the start of these sessions, BIT researchers provided information sheets to magistrates which again informed them their participation was voluntary, that they were able to withdraw from the session if they wished, and that no personally identifiable information from the session would be provided to the Council. Specific consent was obtained from all participants prior to these sessions taking place.

Recruitment for all three research activities relied on participants opting into the activities. It is acknowledged this self-selection approach could have introduced bias into the sample, as these participants could have been more interested, or felt more strongly about, usability issues for the guidelines.

Sampling

Researchers, in agreement with the Council, sought to obtain a purposive sample of 35 unique participants across research activities. Participants had a mix of key characteristics of interest, including age, gender, and judicial role. The regional location of sentencers was not considered to be a key characteristic of interest for this research project, given that all sentencers across England and Wales have access to the same guidelines.

Table 1 provides a summary of the number of participants who took part in research activities based on their role. Note that there were four interview participants who were participants in two types of research activities (virtual usability testing and interview sessions) sessions: two magistrates, one deputy, one district judge and one circuit judge.

Table 1: Number of participants across research activities by judicial role

|

Research activity |

Magistrates |

District/deputy district judges |

Circuit judges |

|

In-person observation |

9 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Virtual usability testing |

9 |

2 |

6 |

|

Interviews |

10 |

1 |

2 |

|

Total |

28 |

3 |

8 |

It is important to note this research explored the usability of the guidelines with a small sample of self-selecting sentencers who are unlikely to be representative of the population of all sentencers. Given the scope of this research project, the sample was not intended to be representative of all sentencers across England and Wales. This means that the findings are indicative only and may mean that not all sentencers may consider the recommendations set out in this report as improving their usability of the guidelines. Further, it is acknowledged this research project involved relatively few judges, compared to magistrates. This may have impacted on the findings with potentially fewer usability issues identified for guidelines used in the Crown Court (compared to the issues identified for guidelines used in the magistrates’ court).

Sample profile

As outlined above, for the virtual usability testing and interview sessions, the online registration form sentencers were asked to complete also asked for some brief advance information. This helped BIT recruit a purposive sample of sentencers with a range of different experiences and circumstances.

This information is presented below. Background information was not collected from participants involved in in-person observation activities, as this research activity focused primarily on exploring how benches of magistrates interacted with guidelines (rather than other characteristics).

Gender and age range

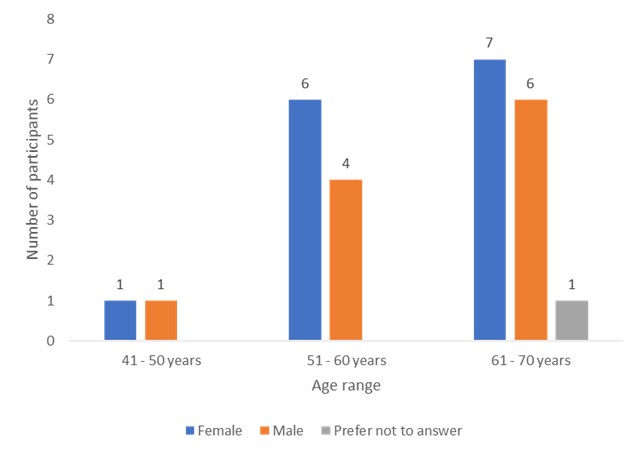

There was a close split between females (n=14; 54 per cent of participants involved in these activities) and males (n=11; 42 per cent of participants), with one participant preferring not to indicate their gender.

The age of participants in virtual usability testing and interview activities (n=26) ranged between 41 and 70 years old, with a majority of participants aged between 61 and 70 years old.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the gender and age ranges of participants.

Figure 1: Age ranges and gender of participants for virtual usability testing and interview activities

Roles

Virtual usability testing and interview activities involved the following number of different types of sentencers:

- 17 magistrates

- one deputy district judge

- one district judge

- seven circuit judges

Confidence in digital literacy

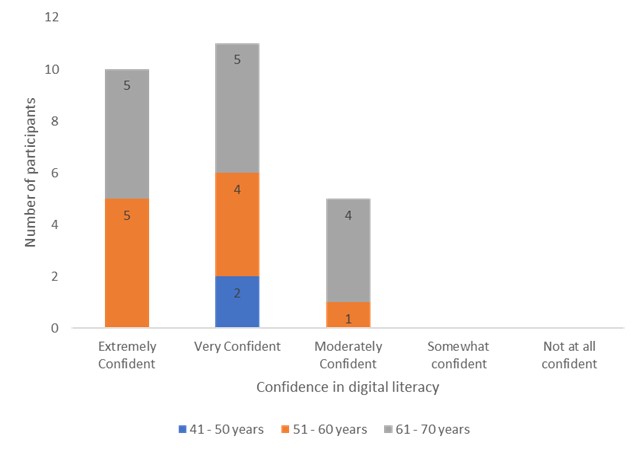

Most participants reported having a relatively high level of digital literacy. Around 80 per cent of participants in virtual usability testing and interview activities rated being ‘very confident’ (n=11) or ‘extremely confident’ (n=10) in using IT services. The remainder of participants rated being ‘moderately confident’ (n=5) in their digital literacy. Figure 2 provides an overview of participants’ self-reported levels of confidence with IT, across different age ranges.

Figure 2: Participants’ ratings of confidence with digital literacy across age ranges

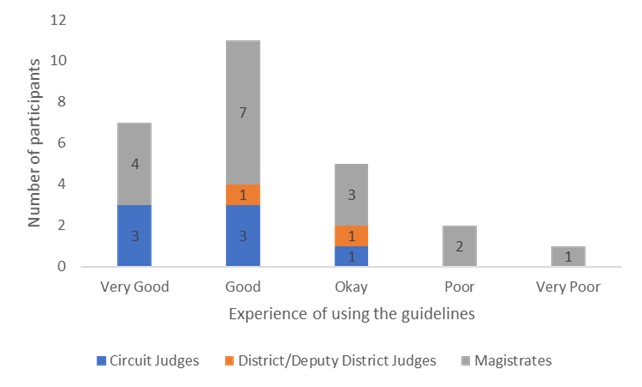

Experience of guidelines

A majority of participants indicated having had a positive experience of using the guidelines. Nearly 70 per cent of participants in virtual usability testing and interview activities rated their experience of using the guidelines as ‘good’ (n=11) or ‘very good’ (n=7). Three participants (11 per cent of participants in virtual usability testing and interview activities) rated their experience of the guidelines as ‘poor’ (n=2) or ‘very poor’ (n=1). Figure 3 provides an overview of different types of sentencers’ ratings of using the guidelines.

Figure 3: Participants’ experience of the guidelines across different types of sentencers

Research activities

In-person observations

These sought to understand the context in which magistrates make decisions, as well as how they interact with the guidelines when making sentencing decisions.

Only magistrates were involved in this stage of the research. This is because observations of judges were included in other research activities and researchers wanted to observe how benches of three magistrates (the usual number of magistrates that sit together in a case) interacted with the guidelines. In doing so, it was possible to observe how guidelines are used in a small group setting (as they would be in real cases) and how easily they can be used and navigated to support collective discussion and decision-making.

Magistrates (n=9) were provided with information about hypothetical cases involving different offences and asked to take the researchers through the stages of their sentencing process in a mock sentencing exercise. Each hypothetical case involved more than one offence, to observe how magistrates interacted with multiple guidelines for a single case. Providing a hypothetical case for magistrates helped researchers observe how groups of magistrates might interact with the guidelines during an actual sentencing decision and identify potential friction points with the useability of the guidelines, including any ways in which participants had managed to work around them. An observational approach also avoided having to rely solely on participants’ recollection of how they use and engage with the guidelines. Following the completion of these hypothetical cases, a brief collective discussion was facilitated by researchers to ask follow-up questions regarding how magistrates had interacted with the guidelines.

Two researchers observed these sessions, with one researcher facilitating the session and another taking notes of how magistrates engaged with the guidelines on their laptops. A wide range of offences were chosen to be discussed across four different hypothetical cases, so that observations could be made of how magistrates used a number of different guidelines:

- Breach of a Community Protection Notice (Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, s.48)

- Common assault (Criminal Justice Act 1988; section 1 Assaults on Emergency Workers (Offences) Act 2018, s.39)

- Criminal damage (Criminal Damage Act 1971, s.1)

- Dangerous driving (Road Traffic Act 1988, s.2)

- Drug driving (Road Traffic Act 1988, s.5A)

- Fear or provocation of violence (Public Order Act 1986, s.4)

- Handling stolen goods (Theft Act 1968, s.22)

- Harassment (Protection from Harassment Act 1997, s.2)

- Possession of a controlled drug (Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, s.5)

- Speeding (Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, s.89(1))

- Vehicle taking without consent (Theft Act 1968, s.12)

Magistrates were not provided with any of these cases prior to the session. Each was presented sequentially for magistrates to work through. Depending on the time taken for each, not all cases were completed in each session.

Each in-person observation session involved a separate bench of magistrates. A total of nine magistrates participated across three sessions, with each session lasting about an hour. For practical reasons, these sessions were held at two magistrates’ courts in London.

Virtual usability testing

The virtual usability testing sessions explored how sentencers (magistrates and circuit judges) access, navigate and use the guidelines, when making sentencing decisions.

Virtual usability testing sessions took place over Microsoft Teams, with each session involving one sentencer and one researcher; they lasted around one hour. Sentencers shared their screens with researchers to show their use of the guidelines during the session.

Sentencers took the researchers through the stages of their sentencing process in relation to mock sentencing exercises based on brief hypothetical scenarios, as well as demonstrating how they interacted with the guidelines in more specific ways. Sentencers were encouraged to ‘think out loud’ during the session, to help researchers understand their experience and expectations when engaging with the guidelines. Researchers also asked follow-up questions about how they interacted with the guidelines.

Six hypothetical scenarios were presented. Five scenarios involved a single offence, in order to observe how sentencers interacted with a single guideline. However, one scenario involved two offences, to observe how sentencers interacted with multiple guidelines for a single case. Offences were chosen that sentencers might routinely use guidelines for, but where the Council knew users might face difficulties accessing them, for example because of common spelling errors, where a search might produce multiple results, or where several offences were covered by one guideline.

The following offences were presented to magistrates across six scenarios:

- Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another (Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, s.5(3))

- Harassment (Protection from Harassment Act 1997, s.2)

- Possession of an article with blade/point on education premises, Criminal Justice Act 1988, s.139A(1))

- Careless driving (Road Traffic Act 1988, s.3)

- Going equipped for theft (Theft Act 1968, s.25)

- Breaching a community order (Sentencing Act 2020, sch. 10)

- Voyeurism (Sexual Offences Act 2003, s.67)

The following offences were presented to circuit judges across six scenarios:

- Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another (Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, s.5(3))

- Inflicting grievous bodily harm (Offences against the Person Act 1861, s.20))

- Possession of an offensive weapon on school premises (Criminal Justice Act 1988 (s.139A(2))

- Arson (Criminal Damage Act 1971, s.1(3))

- Robbery (Theft Act 1968, s.8(1))

- Breaching a community order (Sentencing Act 2020, sch. 10)

- Exposure (Sexual Offences Act 2003, s.66)

A total of 17 participants were involved in these sessions.

Semi-structured interviews

Interviews gathered broader information from sentencers about their experiences using the guidelines.

Questions explored how sentencers use the guidelines, potential barriers to their usability, elements which worked well, and feedback on possible improvements to the guidelines. Interview questions were informed by emerging findings from the in-person observation and virtual usability testing sessions conducted prior to the interviews.

Interviews were conducted over Microsoft Teams, with one researcher interviewing each sentencer in each session. Each interview session lasted around 45 minutes.

A total of 13 sentencers were interviewed. Of these, four had taken part in virtual usability testing sessions. These four sentencers were included in interview sessions in order to further explore their interactions with the guidelines, based on observations researchers had made during their virtual usability testing sessions. They were recruited by taking a convenience sampling approach, whereby researchers asked participants who had taken part in virtual usability testing sessions, if they would also like to take part in interview sessions.

The remaining nine interview participants were not involved in any of the other research activities. This provided feedback on the usability of the guidelines from sentencers who had not participated in any of the research activities so far, so there was no risk of influence of prompts from researchers to consider how they might use the guidelines for specific offences or in specific contexts.

Analysis

Transcriptions and researcher notes from in-person observations, virtual usability testing, and semi-structured interviews, were systematically documented in a structured spreadsheet for analysis. A framework approach was used to triangulate and analyse the qualitative data across all the research activities.

The first step in this approach involved identifying emerging themes through familiarisation with the data. An analytical framework was then created using a series of matrices, each relating to an emergent theme. The columns in each matrix represented the key sub-themes drawn from the findings. The rows represented individual participants who were involved across the different research activities. Data was summarised in the appropriate cell, which resulted in data relevant to a particular theme being easily identifiable. This enabled a systematic approach to analysis that was grounded in participants’ accounts.

The next step of the analysis involved working through the charted data to draw out the range of experiences and participants’ views, while identifying similarities, differences, and links between them. Thematic analysis (undertaken by reviewing theme-based columns in the framework) identified common concepts and themes. Cross-activity analysis (undertaken by comparing and contrasting rows in the framework) allowed for links within research activities to be established and findings to be compared and contrasted with each other.

Throughout the analysis a balance was maintained between deduction (using existing knowledge and the research questions to guide the analysis) and induction (allowing concepts and ways of interpreting experience to emerge from the data).

Due to the large volume of data, a team of three researchers jointly carried out the analysis. Each researcher was allocated several high-level themes and subsequently analysed the relevant data across all research activities to produce sub-themes. Regular meetings were scheduled to discuss emerging themes and ensure a consistent approach to analysis.

Data protection and storage

Information gathered by researchers was stored securely on BIT’s internal IT system. Raw data (comprising the audio and video recordings as well as resultant transcripts and notes made by researchers during the fieldwork sessions and which includes the personal information of sentencers) were not shared with the Council, and remains securely held by BIT. These data will be stored for six months after this report is provided to the Council, after which time the data will be destroyed to protect the confidentiality of research participants.

BIT’s data processing activities were conducted in accordance with BIT’s policies and procedures, to ensure compliance with legislative requirements (including processing Personal Data, as set out in the GDPR UK). Further details on data privacy policies for this project can be found on the Council’s privacy notice, along with BIT’s privacy policy.