1. Introduction

The Sentencing Council for England and Wales was set up in 2010 and produces guidelines for use by all members of the judiciary when sentencing after conviction in criminal cases. The Council promotes a clear, fair, and consistent approach to sentencing by issuing sentencing guidelines and explanatory materials. It has a statutory duty to monitor these sentencing guidelines and to draw conclusions from the information obtained (s129 Coroners and Justice Act 2009).

On 1 October 2018, the Council published the intimidatory offences guidelines, which are a package of five guidelines covering 11 offences, including harassment and stalking offences. The five guidelines are for use in all courts and apply to all adult offenders (those aged 18 or over at the time of sentence). The guidelines came into force on 1 October 2018 and cover:

- a combined guideline covering the offences of harassment, stalking and racially or religiously aggravated harassment/stalking

- a combined guideline covering the offences of harassment (putting people in fear of violence), stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress), and racially or religiously aggravated harassment (putting people in fear of violence)/stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress)

- threats to kill

- disclosing private sexual images

- controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship

The Council developed guidelines to replace the Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guidelines (MCSG) for harassment, harassment (putting people in fear of violence), racially or religiously aggravated harassment, racially or religiously aggravated harassment (putting people in fear of violence) and threats to kill, to provide more detailed guidance as these guidelines were only applicable to the magistrates’ courts.

Additionally, the package introduced new guidelines for stalking, stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress), racially or religiously aggravated stalking, and racially or religiously aggravated stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress), as there were no guidelines previously covering these offences. The guidelines also covered the newer offences of disclosing private sexual images and controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship which were introduced in 2015.

The aims of the guidelines are to ensure that all sentences are proportionate to the offence committed and in relation to other offences.

1.1 Terminology

On 1 August 2023, the Disclosing private sexual images guideline was renamed to the Disclosing or threatening to disclose private sexual images guideline. This is because of an amendment to the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, which meant threats to disclose private sexual photographs and films became an offence in addition to the existing offence of disclosing private sexual images. The only change made to this guideline was to the title. For consistency with the offence covered at the time of publication, and for which any analysis has been conducted for this report, it will be referred to as the Disclosing private sexual images guideline hereafter.

There are two combined guidelines covering multiple harassment and stalking offences. For simplicity, the relevant stated guideline will be referred to by a shortened name, instead of the full list of offences covered by the guideline. The guideline covering harassment, stalking, and racially or religiously aggravated harassment/stalking will be referred to as the Harassment and stalking guideline. The guideline covering harassment (putting people in fear of violence), stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress), racially or religiously aggravated harassment (putting people in fear of violence)/stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress) will be referred to as the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline.

The data sources in this report use different terminology for sentence outcomes. Community orders (COs) are recorded in the Ministry of Justice’s Court Proceedings Database (CPD) as community sentences. Suspended sentence orders (SSOs) are referred to as suspended sentences. For the sake of consistency, we will only refer to community orders (COs) and suspended sentence orders (SSOs) in this report as this more closely aligns with the terminology used in Sentencing Council guidelines.

Additionally, the term ‘custodial sentences’ refers to both SSOs and immediate custodial sentences.

2. Approach

2.1 Aims

One of the Sentencing Council’s statutory duties under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 section 128 is to monitor the operation and effect of its sentencing guidelines and to draw conclusions from this information. To evaluate the operation and effect of the intimidatory offences guidelines, this report will review whether the guidelines may have had any impact on sentencing outcomes and explore whether there were any issues with implementation. Furthermore, it will review whether any changes which have taken place were in line with those outlined in the Sentencing Council’s resource assessment of the intimidatory offences guidelines. These are summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Estimated changes to sentence outcomes as a result of the intimidatory offences guidelines

| Offence(s) | Estimated changes to sentence outcomes |

| Harassment and stalking | No changes to sentence outcomes. |

| Harassment (putting people in fear of violence) and stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm) | No changes as a result of the guideline but a small increase in offenders falling into the highest category of seriousness is anticipated following a statutory maximum sentence increase from 5 to 10 years’ custody. |

| Racially or religiously aggravated harassment/ stalking | A potential increase in sentences for these offences and an increase in sentence lengths for those sentenced to immediate custody, although this was only expected to lead to a small impact as the offences are low volume. |

| Racially or religiously aggravated harassment (putting people in fear of violence) and stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress) | A potential increase in sentences for these offences and an increase in sentence lengths for those sentenced to immediate custody, although this was only expected to lead to a small impact as the offences are low volume.

Any increase as a result of the statutory maximum sentence increase (from 7 to 14 years’ custody) for racially or religiously aggravated harassment (putting people in fear of violence) and stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress) would not be attributable to the guideline. |

| Threats to kill | No changes to sentence outcomes. |

| Disclosing private sexual photographs and films with intent to cause distress | No changes to sentence outcomes. |

| Controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship | No changes to sentence outcomes. |

Source: Sentencing Council’s resource assessment of the intimidatory offences guidelines

Given the data available, this is a descriptive evaluation and it has not been possible to account for the impact of additional factors on sentence outcomes (for example, changes in charging decisions for offences, or other guidelines). It is also not possible to conclude definitively whether the introduction of the intimidatory offences guidelines caused the changes seen in sentence, either in terms of changes to severity of sentencing or consistency in outcomes.

However, by comparing the observed changes in sentencing data and analysing available qualitative sources, the Council can consider whether the guidelines are working as anticipated and decide whether any further work on the intimidatory offences guidelines needs to be conducted. The Council is also continuing to explore options for measuring consistency as part of its wider work (see Annex A for more information).

2.2 Methodology

The Council has taken a mixed methods approach to the evaluation, including quantitative analysis of sentencing data from the Ministry of Justice’s Court Proceedings Database (CPD) and from the Council’s own magistrates’ court data collection, and qualitative analysis of transcripts of Crown Court sentencing remarks and a review of Court of Appeal transcripts.

2.2.1 Ministry of Justice (MoJ) Court Proceedings Database (CPD)

The MoJ’s CPD was used to produce statistics on volumes, outcomes and sentence lengths for all of the intimidatory offences, for the 12 month period before the intimidatory offences guidelines came into effect (July 2017 to June 2018) and the 12 month period afterwards (October 2018 to September 2019). This period excludes the time when the guidelines had been published but were not yet in force. The data was used to observe the changes in the type of principal disposals being imposed and the average custodial sentence length (ACSL) for each of the offences (see Annex A for further information).

For each of the offences, type of disposals imposed and ACSLs were also examined between 2012 and 2022 to review whether any changes were part of a longer term trend. This report includes data up until 2022, as this was the last period of data available at the time of analysis.

For more information on this data source, including limitations, please see Annex A at the end of the report.

2.2.2 Magistrates’ court data collection

A data collection exercise covering the pre guideline and post guideline periods was conducted to further aid our understanding of how these cases are sentenced in courts, and to explore any changes in sentencing practice following the introduction of the intimidatory offences guidelines.

The data collection was undertaken in magistrates’ courts to collect more detailed information on sentencing, for example, on culpability, harm, aggravating and mitigating factors, in addition to sentence starting points and final sentence outcomes. The data collection gathered data on the offences of harassment and stalking, which are summary only offences, typically sentenced in the magistrates’ courts.

The first phase of the data collection ran from 1 November 2017 to 30 March 2018 prior to the implementation of the guideline: referred to as the ‘pre guideline’ period. It was predominantly conducted using online forms, although a small volume of data were collected with paper forms. The second phase of the collection ran from 23 April 2019 to 30 September 2019, after the guideline was in force. This is referred to as the ‘post guideline’ period, and data were collected using online forms only. All sentencers were requested to fill in a form for each harassment and stalking case sentenced in the magistrates’ courts, where the offender was an adult.

It is worth noting that the pre and post guideline periods for the magistrates’ court data collection differ from the pre and post guideline periods used for analysis of the CPD. The magistrates’ court data collections cover a shorter window (approximately 5 months pre guideline and 5 months post guideline) within the CPD pre and post guideline time periods (which each cover a 12 month window).

The figures in Table 2 reflect the number of responses to in the magistrates’ court data collection after data cleaning, where some records were excluded due to not meeting the data collection criteria or due to poor quality (missing or contradictory information within a record). More information on the data cleaning exercise and exclusions has been published alongside this evaluation: Harassment and stalking data collection.

Table 2: Number of responses from the magistrates’ court data collection

| Offence | Pre guideline | Post guideline |

| Harassment | 225 | 271 |

| Stalking | 27 | 61 |

| Total | 252 | 332 |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

The data collection for harassment returned a 13 per cent response rate for the pre guideline period. Post guideline, there was a response rate of 21 per cent.

The data collection for stalking returned a pre guideline response rate of 14 per cent and a post guideline response rate of 27 per cent. Stalking is a much lower volume offence than harassment which means that, although the response rates are similar, the actual number of responses collected for stalking was much lower and caution will therefore need to be taken when interpreting the data. For more information on the limitations of this data source please see Annex A.

Analysis of the data included comparing differences pre and post the guidelines’ introduction for:

- sentence outcomes, including detailed analysis of sentence starting points and final sentence outcomes

- types of factors considered in sentencing the offender (culpability, harm, aggravating factors, mitigating factors)

- the distribution of offending in terms of seriousness, culpability, and harm

2.2.3 Crown Court sentencing transcripts

Sentencing remarks are given by the judge at the final stage of the sentencing process and provide an explanation of the reasons behind a sentence that has been imposed. These can therefore provide more insight as to both how and why a particular sentence outcome was arrived at, and how the guideline has been used in practice.

A content analysis was conducted on a small sample of transcripts of judge’s sentencing remarks for the either-way intimidatory offences:

- Harassment (putting people in fear of violence)

- Stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress)

- Racially or religiously aggravated harassment/stalking

- Racially or religiously aggravated harassment (putting people in fear of violence)/stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress)

- Threats to kill

- Disclosing private sexual photographs and films with intent to cause distress

- Controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship

These offences can be heard in the magistrates’ courts or the Crown Court, but sentencing remarks are only available at the Crown Court. This means any sample of transcripts for these offences would not reflect all offending and instead would likely reflect the more severe end of sentencing. No transcripts for harassment or stalking were analysed, as these are summary only offences and transcripts are not available in magistrates’ courts.

Analysis of these transcripts differed between offences depending on the volume of transcripts, with sample sizes ranging from 13 to 34.

For most offences a random stratified sampling method was used to select a sample that represented the range of sentence outcomes and custodial sentence lengths received. However, for some offences, the sample was selected to include particular types of cases; for example, for offences where the statutory maximum sentence changed, cases receiving the longest custodial sentences were oversampled. This was to ensure that cases of specific interest were sampled in high enough volumes to be able to explore any potential issues. The specific approach to the transcript sampling has been included within the discussion of offence specific findings.

Transcripts were ordered from 2019 and 2020 to examine any issues with the introduction of the intimidatory offences guidelines. Analysis included:

- reviewing the frequency of factors (for example, culpability, harm, mitigating and aggravating) post guideline, to help understand what types of cases fell into the different culpability and harm categories, and

- reviewing potential implementation issues with the guidelines, for example, whether the additional steps required for the racially or religiously aggravated offences were followed as stated by the guidelines

2.2.4 Court of Appeal transcripts

Content analysis of Court of Appeal judgments was also conducted to investigate whether the reasons put forward for any appeals against sentences related to the implementation of the guideline. A small sample of ten successful appeals from 2022 were reviewed for the available offences: harassment (putting people in fear of violence), stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress), racially or religiously aggravated harassment, threats to kill and controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship.

Analysis involved reviewing whether the reason for the appeal and the explanation for the successful appeal included references to specific features of the sentencing guideline. For example, reviewing whether there were difficulties in interpreting particular factors in the guideline.

2.3 General conventions

2.3.1 Rounding

For figures reported from the CPD, actual numbers of sentences have been rounded to the nearest 100 when more than 1,000 offenders were sentenced, and to the nearest 10 when fewer than 1,000 offenders were sentenced. An exception is when reporting on the sample or population totals underneath graphs and figures, where the actual total has been stated. Proportions of sentencing outcomes have been rounded to the nearest integer.

Percentages in this report may not appear to sum to 100 per cent, due to rounding. Percentages have been rounded to the nearest integer. Percentage point differences may not sum to zero as they have been calculated using unrounded percentages.

2.3.2 Interpretation of the tables and graphs

For each table and graph, the data source (CPD, magistrates’ court data collection etc) will be indicated underneath.

Throughout the report, different time periods are presented, for example, monthly, quarterly or yearly, and these are stated in the table or graph title. If a specific time period e.g. ‘pre guideline’ or ‘post guideline’ has been used, the time period and base sizes will be stated underneath the table or graphic e.g. ‘Pre guideline period covers 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 (N=487), post guideline period covers 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 (N=595)’.

If a time period in a table crosses more than one year (e.g. 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019) then figures relating to this time period will not be directly comparable to a graph where data is based on a total monthly, quarterly or yearly volume or proportion.

In graphs which are representing a monthly, quarterly or yearly time period, each data point (a dot on the graph) represents the total number or proportion for the month, quarter or year. This means when interpreting changes in the graph, if a proportion is e.g. 50 per cent in September, and 60 per cent in October and there is a line joining the two data points, this should be interpreted as there being a higher proportion in October, not that there was a steady increase across or between September and October.

3. Offence specific findings

The offences of harassment, stalking and racially and religiously aggravated forms of these offences are all covered under one guideline, and the equivalent offences of harassment (putting people in fear of violence) and stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress) and the racially and religiously aggravated forms are all covered under another singular guideline. However, as the impact of these guidelines on sentencing practice for each offence may differ, each offence has been examined separately.

In this section, findings for harassment and then stalking are first discussed, followed by harassment (putting people in fear of violence) and stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress). Following these sections, there are two sections covering the racially and religiously aggravated forms of the aforementioned offences. The racially and religiously aggravated forms of harassment and stalking were considered together, as they were not split by harassment and stalking in the data in the Court Proceedings Database (CPD). Following these sections, the offences of threats to kill, disclosing private sexual photographs and films with intent to cause distress are discussed, as well as controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship.

Some of the data presented in this report covers the period from March 2020 in which restrictions were in place on the criminal justice system due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (see Annex A for further details). For relevant offences, where the data indicates sentencing may have been impacted by COVID-19 and where these changes may affect the interpretation of the impact of the guidelines, the impact of COVID-19 has been discussed.

Many of the offences covered by the intimidatory offences guidelines are often conducted in a domestic context. The Domestic Abuse Overarching Principles guideline (Domestic abuse guideline hereafter) came into force in May 2018, six months before the intimidatory offences guidelines, and it is possible that this guideline may have had an impact on the sentencing of some of these offences, as courts reflected the domestic abuse context that may have been present within some of the offending. Please see the Research review of the Overarching principles: domestic abuse guideline for more information on the impact of this guideline.

Additionally, this report discusses the potential impacts of the Imposition of community and custodial orders guideline that came into force on 1 February 2017 (the Imposition guideline hereafter).

Given the timing of the in force date for the Imposition guideline, it is possible that any impacts of that guideline may overlap with those associated with the intimidatory offences guidelines. Further discussion of any potential overlap between the two guidelines will be covered in relevant offence specific sections. This will not cover any small changes to the intimidatory offences guidelines that have been introduced since October 2018, and which are not expected to have had a substantial impact on sentencing outcomes.

3.1 Harassment

3.1.1 Summary of findings

- For the offence of harassment there was an increase in community orders (COs) as a sentence outcome, and a corresponding decrease in suspended sentence orders (SSOs) and fines after the Harassment and stalking guideline came into force, despite no intention for the guideline to change sentencing practice.

- Some modest changes in sentencing outcomes emerged following the publication of a letter in April 2018 reminding sentencers about the principles of the Imposition guideline. Following the introduction of the Harassment and stalking guideline a further increase was seen in the proportion of COs, and a decrease in SSOs.

- No substantial or sustained changes to the mean average custodial sentence length (ACSL) were seen post guideline for harassment, suggesting the guideline did not have an impact on the length of custodial sentences issued.

3.1.2 Background

The offence of harassment (Protection from Harassment Act 1997, s.2) is a summary only offence, with a statutory maximum sentence of 6 months’ custody. Prior to the Harassment and stalking guideline coming into force on 1 October 2018, there was a Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guideline (MCSG) for harassment, which had been in force from 4 August 2008.

The Sentencing Council’s resource assessment of the intimidatory offences guidelines stated the aim of the guideline was to improve consistency of sentencing and to maintain current sentencing practice for harassment. There was no intention to change the use of disposal types, and the sentencing ranges in the Harassment and stalking guideline were set with current sentencing practice for harassment in mind. Furthermore, consultation stage research suggested sentencing levels for harassment were similar under the MCSG for harassment and the new Harassment and stalking guideline. Overall, the resource assessment anticipated there would be no impact on prison and probation resources as a result of the introduction of the Harassment and stalking guideline for harassment.

3.1.3 Trend analysis

Sentence volumes

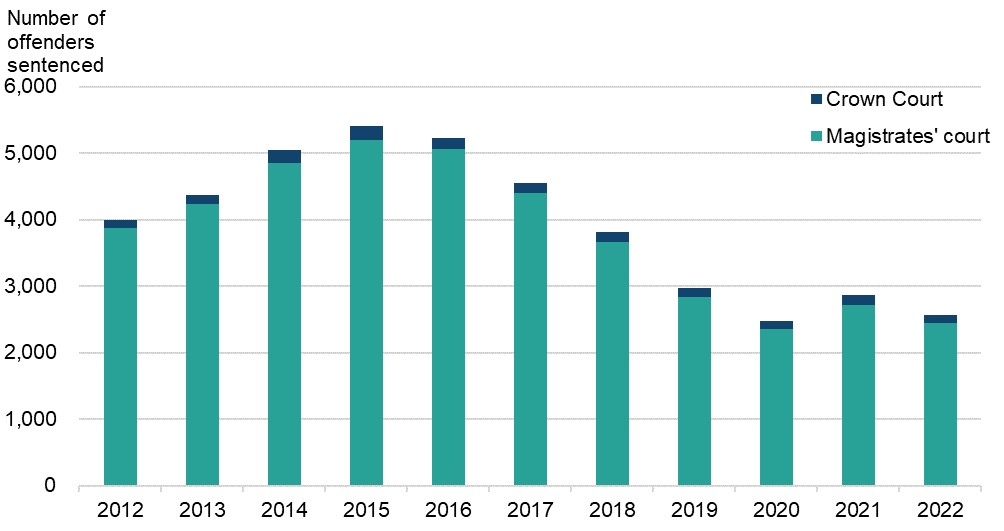

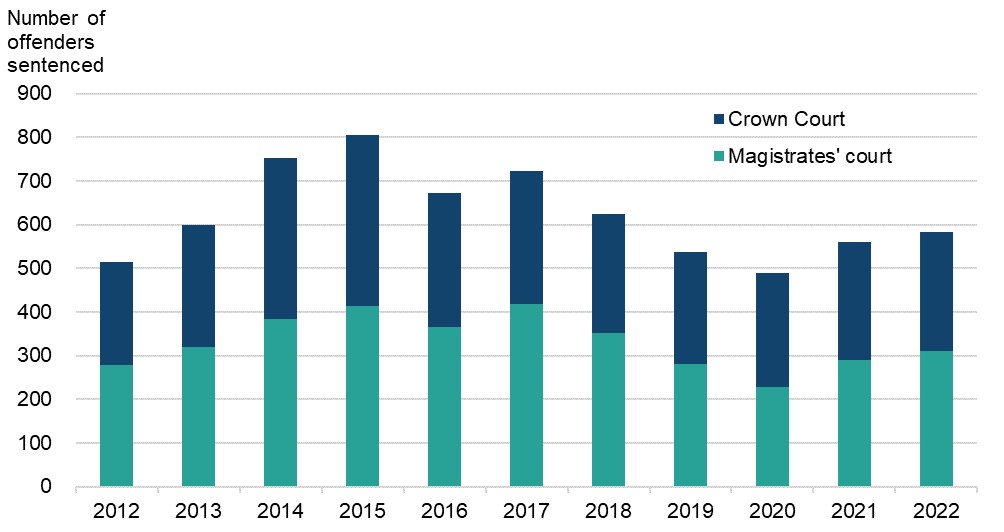

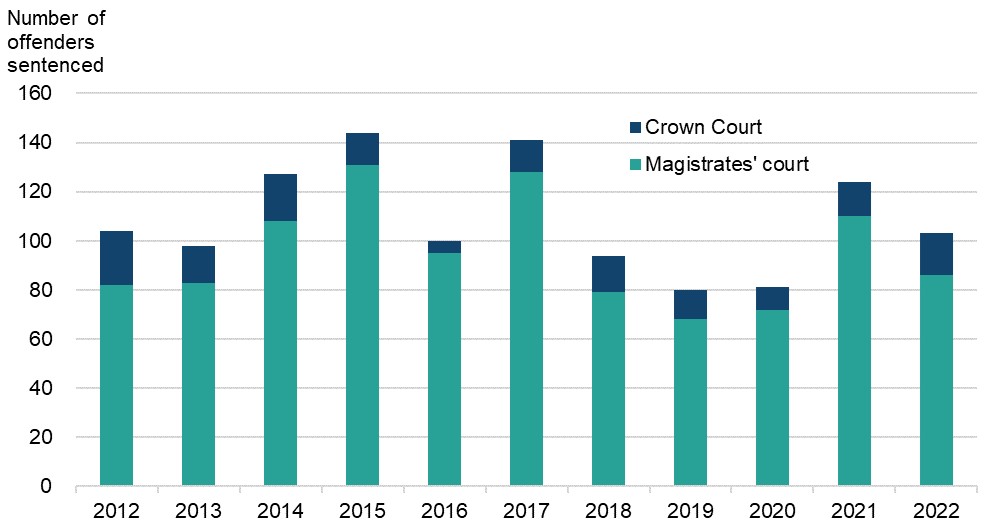

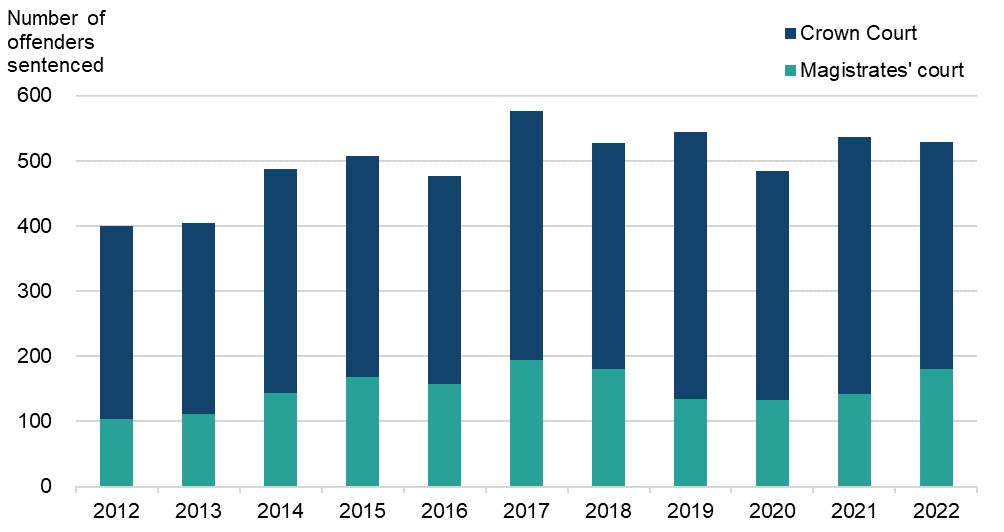

Harassment is the highest volume offence covered by the intimidatory offences guidelines. The number of offenders sentenced for this offence has been steadily declining since 2015 when volumes peaked at 5,400 (Figure 1) and were already in decline when the guideline came into force in October 2018. The majority of offenders are sentenced at magistrates’ courts as harassment is a summary only offence.

Figure 1: Number of adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by court type, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Sentence outcomes

Analysis using the Court Proceedings Database (CPD) was conducted to compare sentence outcomes in the pre guideline period (1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018) with those in the post guideline period (1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019). The figures in Table 3 indicate the Harassment and stalking guideline may have contributed to some changes in sentencing practice contrary to the expectations outlined in the intimidatory resource assessment.

Table 3: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by sentence outcome, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable, k2 = less than 0.5 percentage point difference.

| Sentence outcome | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 10% | 11% | 2 ppts |

| Fine | 20% | 16% | -4 ppts |

| Community order | 43% | 52% | 9 ppts |

| Suspended sentence order | 15% | 9% | -7 ppts |

| Immediate custody | 11% | 10% | -1 ppt |

| Other/unknown | 1% | 1% | [k2] |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Pre guideline period covers 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 (N=4,332), post guideline period covers 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 (N=3,153). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

In the year following the guideline coming into force there was a 9 percentage point increase in community orders (COs). There was also a decrease in suspended sentence orders (SSOs) (7 percentage points) and fines (4 percentage points) for those sentenced for harassment, as compared with the pre guideline period.

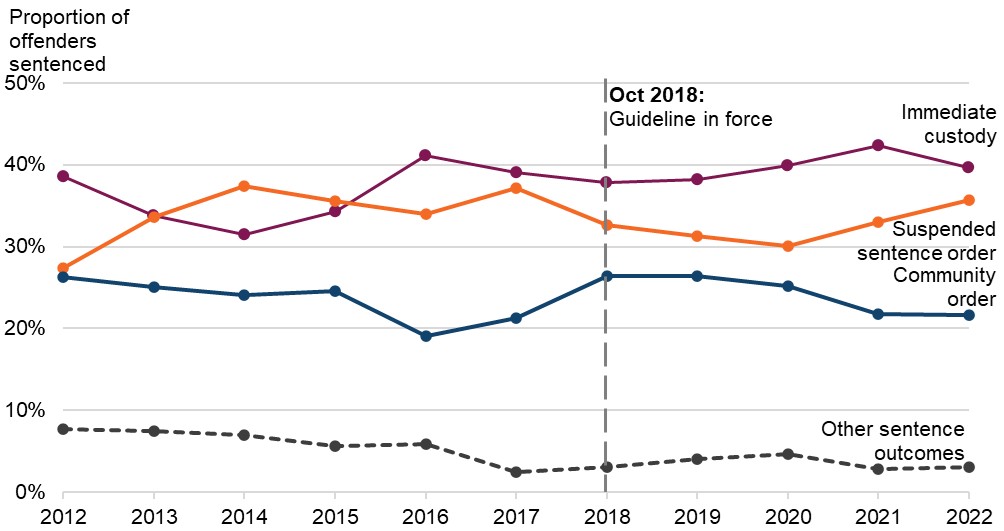

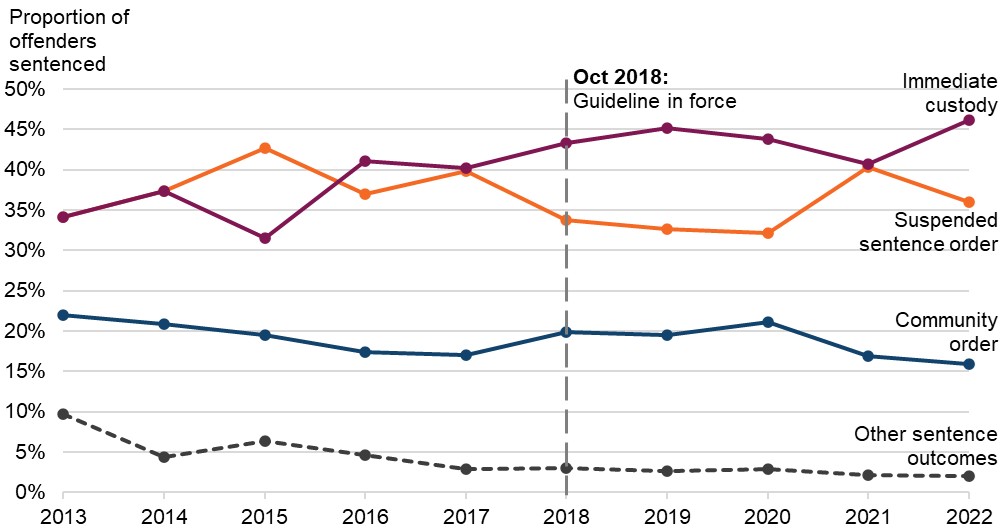

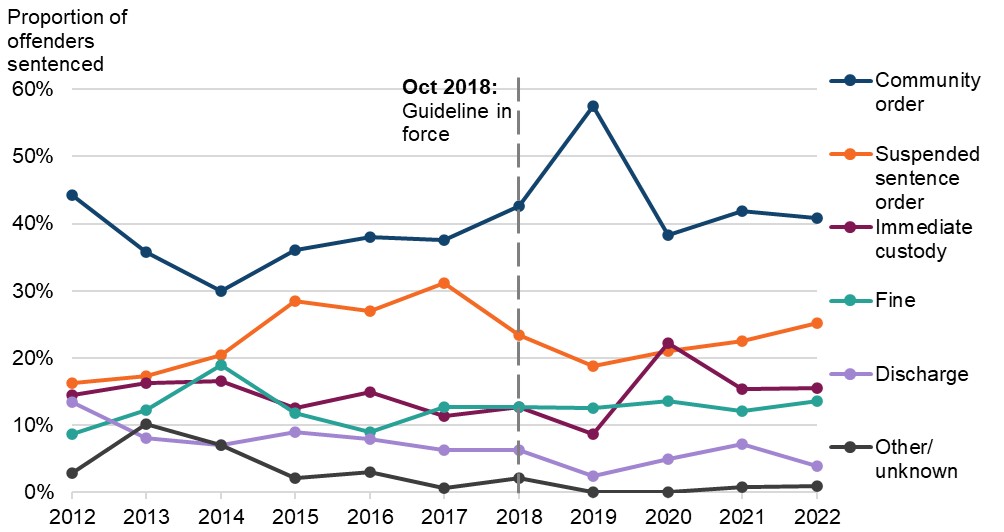

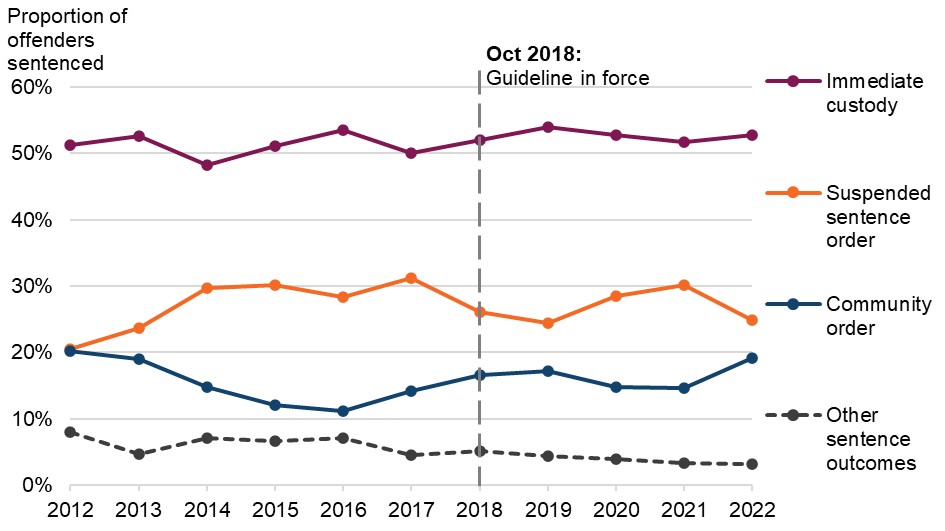

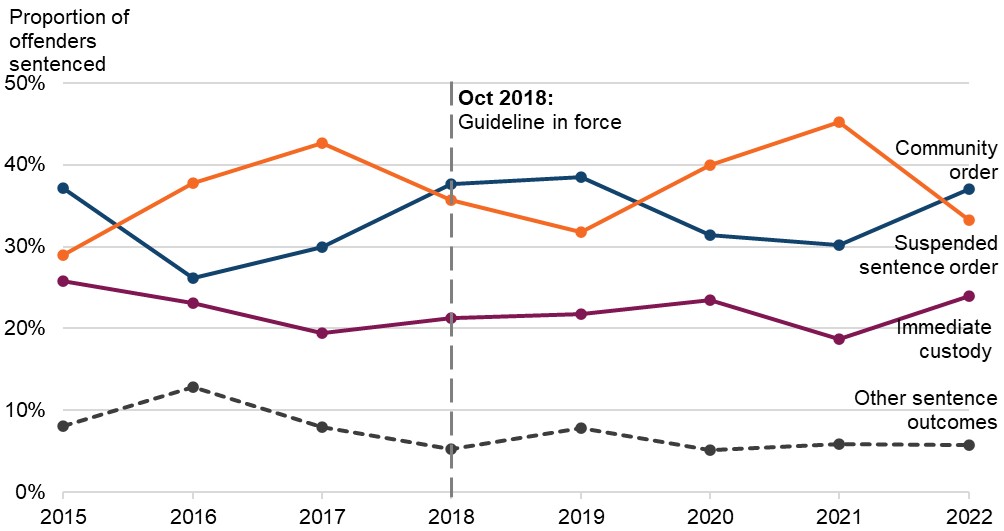

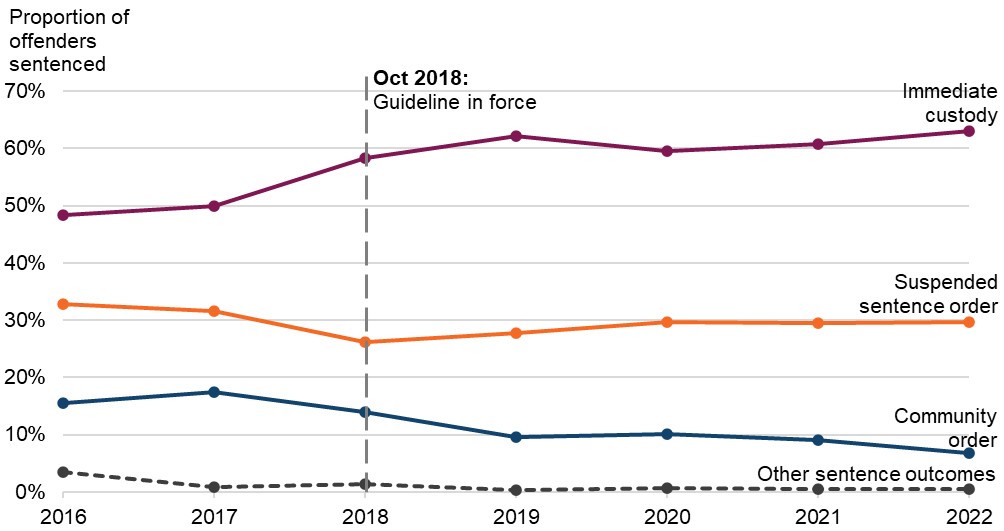

The changes in the proportion of sentence outcomes seen in the post guideline period persist beyond the immediate year following the introduction of the Harassment and stalking guideline (see Figure 2). In 2022, the proportion of COs issued remained at approximately 50 per cent, similar to the proportion of COs issued in the post guideline period of 52 per cent. The proportion of SSOs, which decreased in the post guideline period to 9 per cent, increased again slightly in 2020 but remained at around 11 per cent in 2022, a lower proportion compared with the pre guideline period (15 per cent).

Figure 2: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by sentence outcome, by year, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Given the unanticipated changes seen in sentence outcomes, another factor was considered which may have contributed over this time period to this pattern in sentencing: the Imposition guideline. The Imposition guideline originally came into force on 1 February 2017. It was developed in part to ensure sentencers were not using SSOs as a more severe form of a CO, where the custody threshold had not been crossed. As stated in the Imposition guideline resource assessment the introduction of the Imposition guideline was therefore expected to have the impact of reducing the number of SSOs imposed, leading to a corresponding increase in COs.

However, a review of the Imposition guideline found that it did not appear to have an impact on sentencing outcomes immediately, and an impact was instead observed from April 2018 following a letter being sent to all sentencers from the then Chairman of the Sentencing Council, reinforcing the aim of the guideline. In the review of the Imposition guideline, this was evidenced by a decrease in the use of SSOs and an increase in COs, particularly for triable either way offences at this point in time. This matches the pattern seen for harassment.

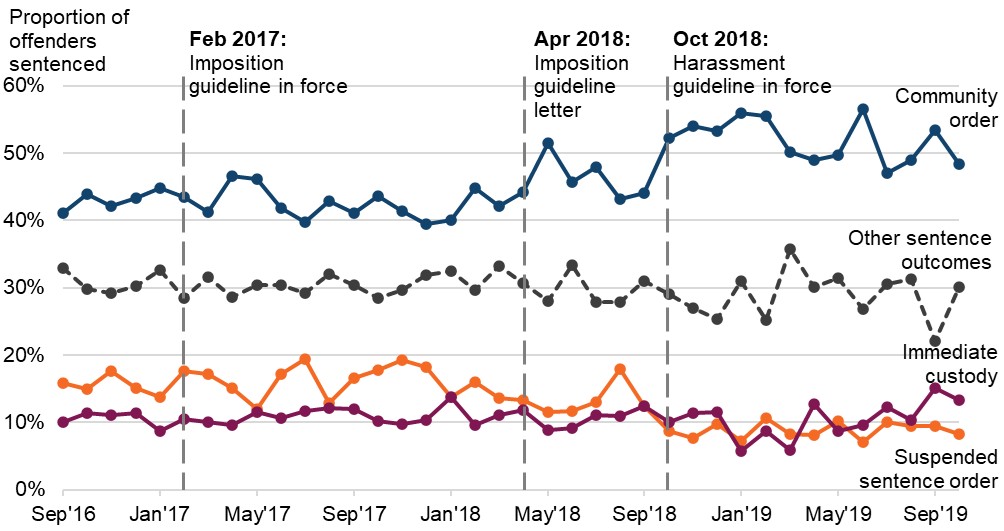

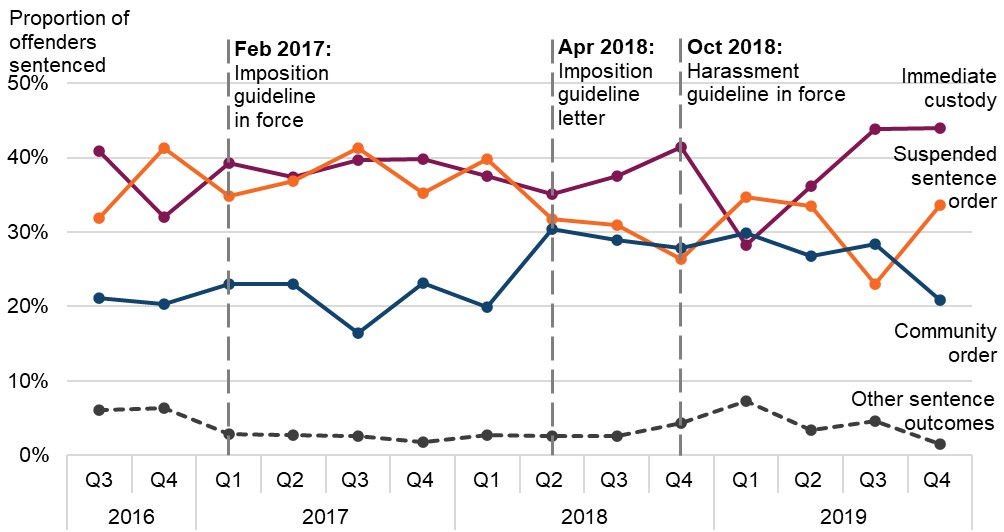

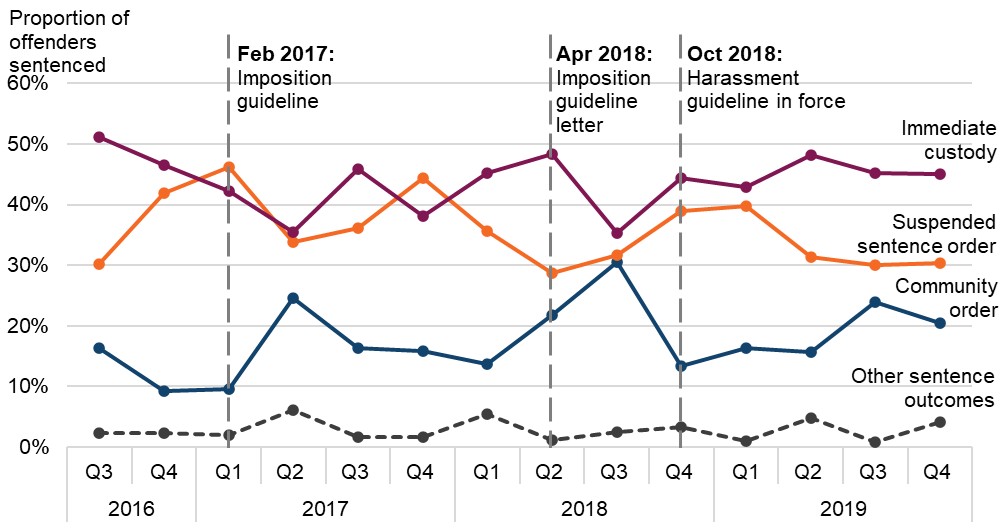

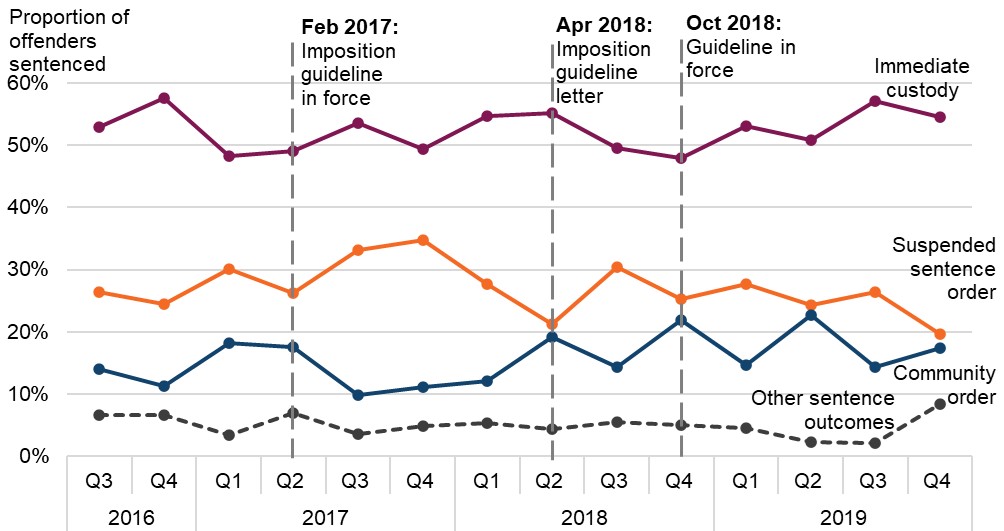

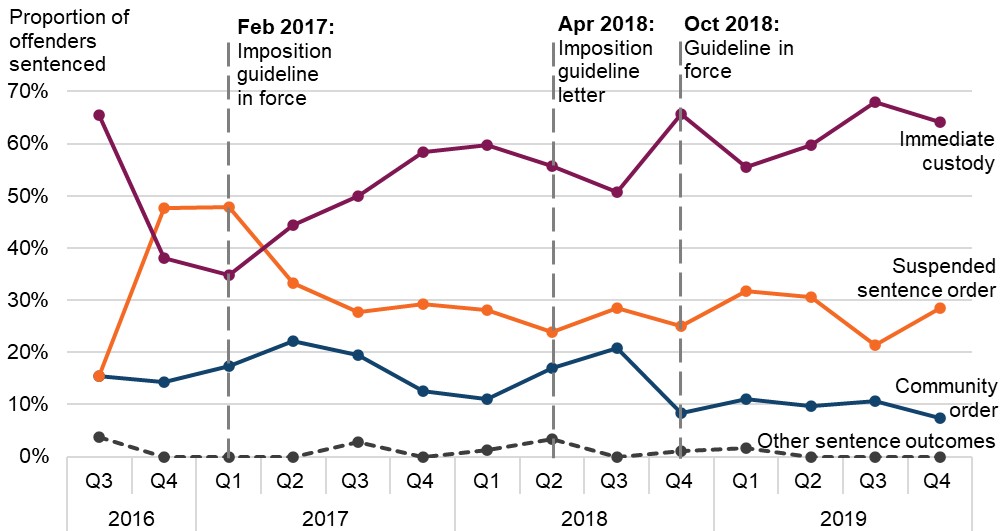

To examine in more detail if the Imposition guideline may have impacted sentence outcomes for this offence, the CPD data were examined on a monthly basis between September 2016 and October 2019 (see Figure 3). Presenting data at this level inevitably means lower volumes for each data point. Therefore, examining trends over several months provides a more reliable indicator that the change is not due to general fluctuations as a result of low volumes.

A modest increase in the proportions of COs received can be seen across April 2018 to September 2018, the period following the publication of the Imposition guideline letter. However, when the Harassment and stalking guideline came into force (October 2018) a greater increase in COs (and a decrease in SSOs) can be seen, which is then broadly maintained in the period following.

Figure 3: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by sentence outcome, by month, September 2016 to October 2019

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

While it is not possible to determine how much of the change in sentence outcomes was due to the Imposition guideline letter compared with the Harassment and stalking guideline, there was a clear change following the introduction of the Harassment and stalking guideline. This suggests this guideline contributed to some of the changes in sentencing practice for harassment, which was not anticipated in the resource assessment.

It is also worth noting that the Domestic abuse guideline came into force on 24 May 2018, the same year as the intimidatory offences guidelines came into force and also when the impact of the Imposition guideline was seen. The review of the Domestic abuse guideline found that a higher proportion of sentencers reported increasing the sentence of a harassment case in some way due to the offence being committed in a domestic context following the introduction of the Domestic abuse guideline. However, it should be noted that there were limitations of this analysis (for further information on the analysis and limitations please see section 3.3.5 of the review of the Domestic abuse guideline).

The analysis in this report of sentencing outcomes post guideline for harassment has not indicated an overall increase in the proportion of more severe outcomes (e.g. custody) and a decrease in less severe outcomes (e.g. COs or fines). However, it is possible that the impact of the Imposition guideline and then the Harassment guideline itself has masked any changes resulting from the Domestic abuse guideline. Alternatively, it is possible the proportion of cases which are committed in a domestic context and the changes as a result to the sentence are not substantial enough to see a definitive change in sentencing practice for harassment overall.

Sentence lengths

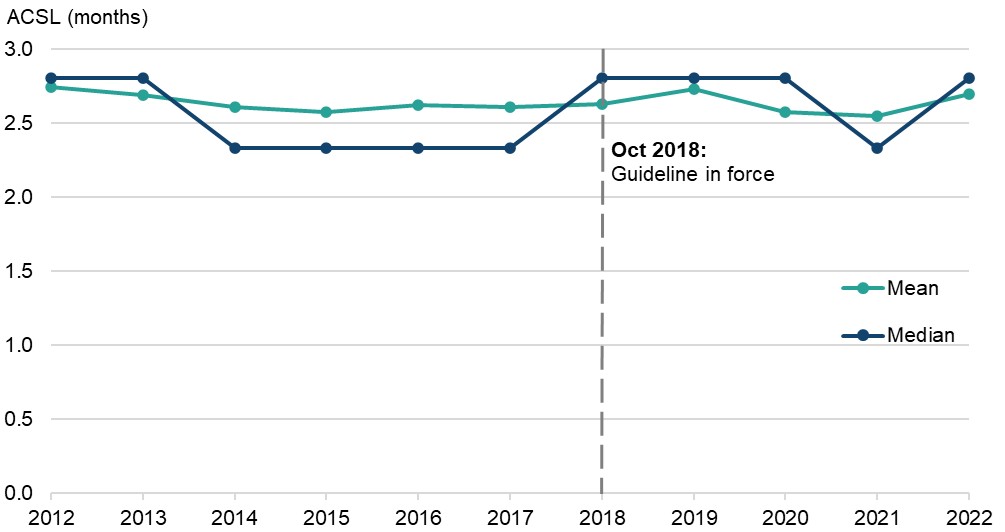

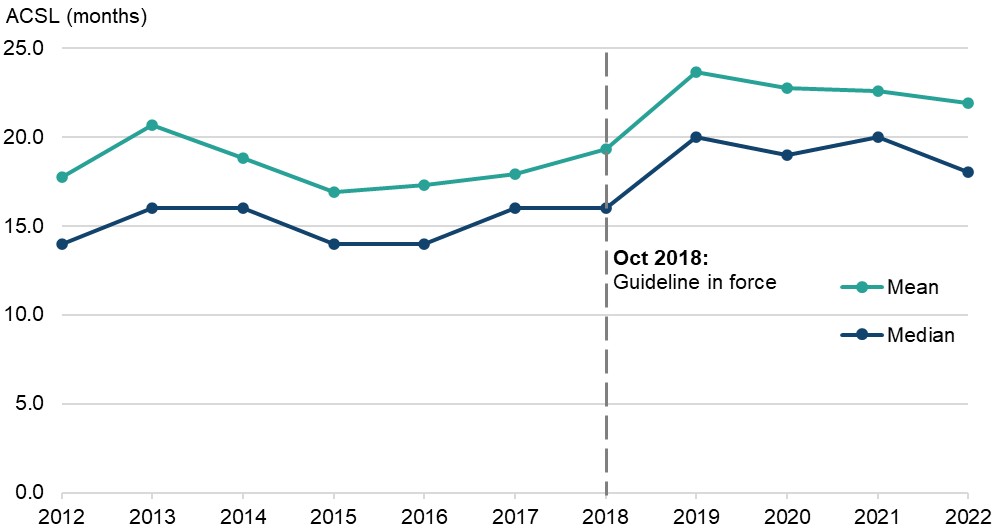

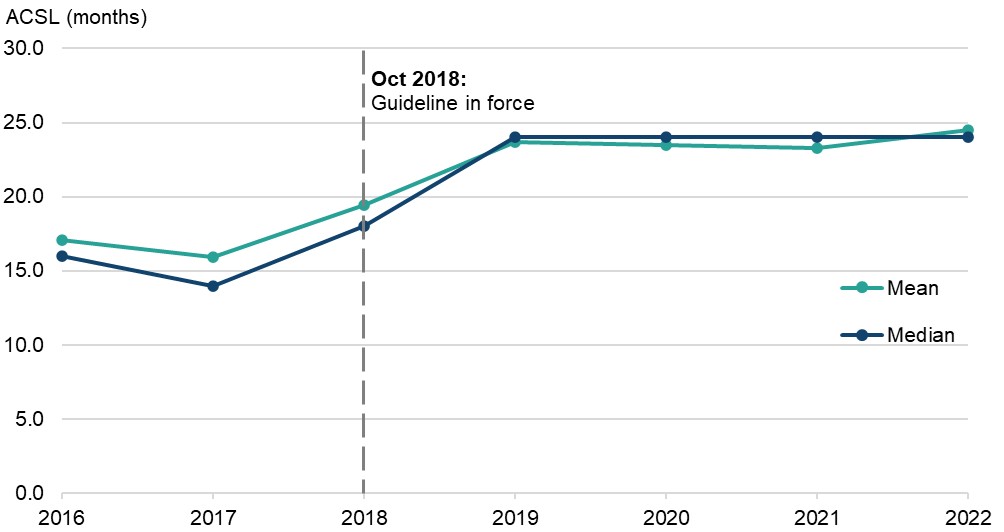

Another element of sentencing which could be impacted by the guideline is immediate custodial sentence lengths. The proportion of immediate custodial sentences for harassment remained relatively stable over time and these account for a relatively low proportion of sentence outcomes (around 10 to 13 per cent of any given year). However, an analysis of mean and median ACSLs was conducted to examine whether the lengths of immediate custodial sentences changed post guideline (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average custodial sentence length (ACSL) in months received by adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by year, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Records over the statutory maximum sentence of 6 months were excluded from analysis.

As can be seen, the mean and median ACSLs were relatively stable between 2012 and 2022 (between 2 and 3 months), and no clear changes occurred in the period following the introduction of the guideline. This suggests it did not have an impact on the lengths of immediate custodial sentences issued for harassment, in line with the intimidatory offences resource assessment.

3.1.4 Guideline review

To understand why sentencing practice may have changed following the introduction of the Harassment and stalking guideline, differences between the previous and existing guideline were reviewed.

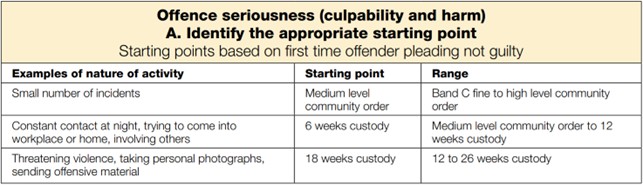

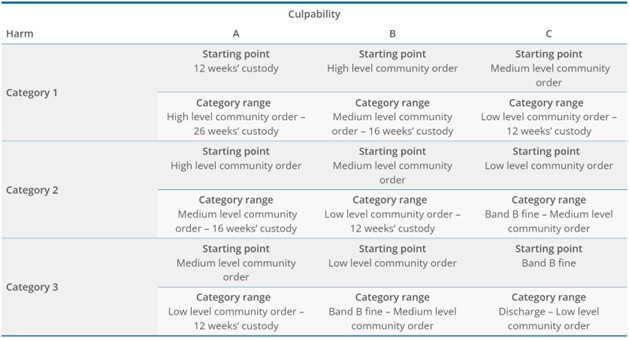

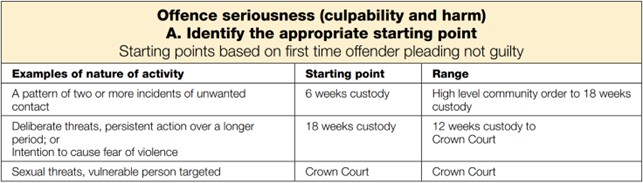

The MCSG for harassment had a three box sentencing grid, with starting points of a medium level CO, 6 weeks’ custody, and 18 weeks’ custody (Figure 5). The table ranged from a band C fine to 26 weeks’ custody.

Figure 5: The MCSG sentencing table for harassment

Source: Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guidelines from the National Archive

In contrast, the Harassment and stalking guideline has three levels of culpability and three levels of harm, which produces a nine box sentencing grid (Figure 6). The starting points range from a band B fine to 12 weeks’ custody. The overall sentencing range of the table is from a discharge to 26 weeks’ custody.

Figure 6: The sentencing table from the Harassment and stalking guideline

Source: Harassment and stalking guideline from the Sentencing Council website

It is possible the changes in proportions of some disposals are related to the proportion of different starting points in the existing guideline: seven of the nine starting points (78 per cent) are COs, compared with only one of the three starting points (33 per cent) in the previous guideline and there is only one custodial starting point, compared to two in the previous guideline. Additionally, all the category ranges in the existing guideline include COs, compared with two of the three ranges in the MCSG sentencing table.

To explore whether the increase in CO sentencing options has led to the increased proportion of CO sentences observed, the starting points and final sentence outcomes pre and post guideline for harassment cases from the magistrates’ court data collection data were analysed.

3.1.5 Magistrates’ court data collection analysis

The magistrates’ court data collection returned a low response rate (please see section 2.2.2 for information on the data collection methodology and response rates). As seen in Table 4, the sentencing outcome distribution seen in the magistrates’ court data collection broadly reflects the distribution seen in the CPD data (Table 3). This suggests any findings from the data collection analysis can be viewed as broadly representative of overall sentencing seen for this offence. It should be noted the time periods covered by the CPD analysis and the magistrates’ court data collection are slightly different (please see sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 for more detailed information on the time periods covered).

Table 4: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by sentence outcome, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable.

| Sentence outcome | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 12% | 10% | -1 ppt |

| Fine | 21% | 18% | -3 ppts |

| Community order | 38% | 52% | 14 ppts |

| Suspended sentence order | 16% | 7% | -9 ppts |

| Immediate custody | 12% | 11% | -2 ppts |

| Other/unknown | 1% | 1% | 1 ppt |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

Pre guideline period covers 1 November 2017 to 30 March 2018 (n=225), post guideline period covers 23 April 2019 to 30 September 2019 (n=271). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

Table 4 shows there was a large increase (14 percentage points) in CO outcomes post guideline, while there was a decrease in both custodial outcomes (9 percentage points for SSOs, 2 percentage points for immediate custody) and fines (3 percentage points).

When looking at the starting points, it can be seen that the 14 percentage point increase in CO outcomes post guideline was not matched by a corresponding increase in CO starting points, of which the proportion only increased by 2 percentage points (Table 5). This small increase in the proportion of CO starting points post guideline is despite there being an increase in CO starting points in the existing guideline (seven out of nine starting points) compared with the MCSG for harassment (one out of three starting points).

Table 5: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment, by starting point, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable.

| Starting point | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 2% | 3% | 1 ppt |

| Fine | 6% | 20% | 14 ppts |

| Community order | 58% | 60% | 2 ppts |

| Custody | 31% | 16% | -15 ppts |

| Other/unknown | 3% | 1% | -2 ppts |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

Pre guideline period covers 1 November 2017 to 30 March 2018 (n=225), post guideline period covers 23 April 2019 to 30 September 2019 (n=271). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

Table 5 shows that the greatest changes to starting points post guideline were in relation to fines and custodial sentences. Post guideline, there was a 14 percentage point increase in fine starting points (from 6 per cent pre guideline to 20 per cent post guideline). This is likely the result of a fine starting point being available under the Harassment and stalking guideline for the first time, as the previous MCSG for harassment did not include any fine starting points (although a fine was included in the sentence range for the lowest level of seriousness).

Conversely, custodial starting points decreased by 15 percentage points, from 31 per cent pre guideline to 16 per cent post guideline. The decrease in custodial starting points is likely due to the fact that under the new guideline only the most serious offending would receive a custodial starting point, as there is only one custodial starting point under the guideline, which is in category ‘A1’; under the MCSG for harassment two thirds of sentence starting points were custodial.

As stated above, in relation to Figure 6, a possible explanation for the increase in CO outcomes, despite little change in the proportion of starting points is the fact that for most of the CO starting points, the bottom of the sentence range in the guideline includes a CO. This limits the opportunity to reduce the sentence below a CO in all but the very lowest level of cases (under the new guideline, of the seven CO starting points, only two include a range that go below a CO). Pre guideline, under the MCSG, there was only one offence category with a starting point of a CO, and this included a lower sentence range of a band C fine up to a high level CO (HLCO).

As Tables 6 and 7 show, a higher proportion of offenders who received a CO starting point post guideline went on to receive a CO sentence outcome (80 per cent) compared with pre guideline (57 per cent). In addition, there was a decrease post guideline in the proportion of offenders who received a CO starting point who went on to receive a discharge (10 percentage points) or fine (17 percentage points).

The decrease in the proportion of offenders who received a CO starting point, but went onto receive a discharge or fine may explain why the proportion of fine starting points increased, but the proportion of fine outcomes did not. If the proportion of offenders who received a fine outcome (from a CO starting point) has decreased, this may have offset any increase in fine outcomes resulting from the increase in fine starting points.

Table 6: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment who received each sentence outcome, by starting point, pre guideline

| Starting point | Absolute or conditional discharge | Fine | Community order | Custody | Other/ unknown | Total |

| Fine | 14% | 86% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Community order | 14% | 24% | 57% | 5% | 1% | 100% |

| Custody | 1% | 0% | 16% | 81% | 1% | 100% |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

Pre guideline period covers 1 November 2017 to 30 March 2018 (n=225). Absolute or conditional discharge and other/unknown starting points are not included in this table, as the number of offenders who received each was fewer than 10. Percentage totals may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

Table 7: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment who received each sentence outcome, by starting point, post guideline

| Starting point | Absolute or conditional discharge | Fine | Community order | Custody | Other/ unknown | Total |

| Fine | 22% | 65% | 7% | 4% | 2% | 100% |

| Community order | 4% | 7% | 80% | 7% | 1% | 100% |

| Custody | 2% | 2% | 16% | 80% | 0% | 100% |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

Post guideline period covers 23 April 2019 to 30 September 2019 (n=271). Absolute or conditional discharge and other/unknown starting points are not included in this table, as the number of offenders who received each was fewer than 10. Percentage totals may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

3.2 Stalking

3.2.1 Summary of findings

- A similar change in sentencing practice was seen to have occurred post guideline for stalking as was seen for harassment. There was an increase in the proportion of offenders receiving COs, and a decrease in the proportion of offenders receiving SSOs after the guideline came into force.

- However, there were also some changes to sentencing seen pre guideline, which may have been tied to the Imposition guideline.

- Due to low volumes of returns for the magistrates’ court data collection, more in depth analysis was not possible. However, some of the data indicates that the increase in COs as a final sentence outcome appears to be due to the increased opportunities for receiving a CO starting point under the Harassment and stalking guideline when compared to the previous Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guideline.

- Overall, it is not possible to determine the degree to which the changes seen were specifically due to the guideline compared with other factors.

- While proportions of immediate custodial sentences remained relatively stable, there was a very slight decrease in ACSLs for stalking across 2018 to 2022. However, it is unclear what may be driving this, and it was concluded the guideline has not impacted custodial sentence lengths.

3.2.2 Background

Stalking was enacted as an offence on 25 November 2012, contrary to section 2A of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 following an amendment by the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012; it has a statutory maximum sentence of 6 months’ custody, the same as harassment. Prior to the introduction of the Harassment and stalking guideline coming into force on 1 October 2018, there was no previous guideline for this offence. However, there is some evidence, both from research with sentencers at the consultation stage of developing these guidelines and from the magistrates’ court data collection, which suggested that the MCSG guideline for harassment was widely used when sentencing stalking cases.

The intimidatory offences resource assessment estimated that, as with harassment, there would be no impact of the guideline on sentencing outcomes. The intent with the Harassment and stalking guideline was to maintain similar sentencing practice and promote consistency in sentencing. Additionally, whilst stalking and harassment are both covered under the same guideline, the resource assessment anticipated that offenders sentenced for stalking would continue to receive slightly higher sentences than harassment.

3.2.3 Trend analysis

Sentence volumes

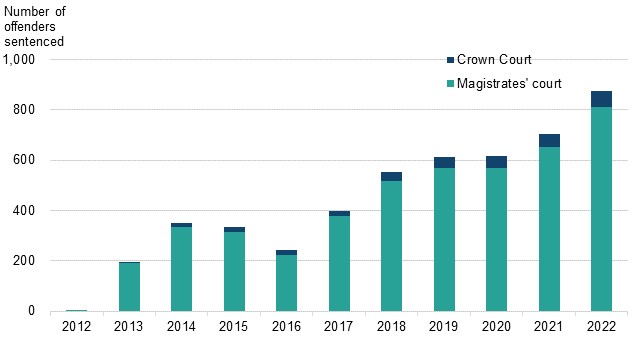

The number of offenders sentenced for stalking has broadly increased year on year since the introduction of the offence, with around 880 offenders sentenced in 2022. Volumes appear to have increased in particular from 2016 onwards. It is a summary only offence and, as such, cases are usually sentenced at the magistrates’ courts.

Figure 7: Number of adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by court type, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Sentence outcomes

Sentence outcomes from the MoJ CPD were analysed, comparing the pre and post guideline periods (Table 8). The changes in sentencing outcomes for offenders sentenced for stalking show a similar pattern to those sentenced for harassment, with an increase in COs (10 percentage points) and a decrease in SSOs post guideline (9 percentage points).

Table 8: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by sentence outcome, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable, k3 = less than -0.5 percentage point difference.

| Sentence outcome | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 5% | 5% | [k3] |

| Fine | 8% | 6% | -2 ppts |

| Community order | 45% | 55% | 10 ppts |

| Suspended sentence order | 26% | 17% | -9 ppts |

| Immediate custody | 14% | 16% | 2 ppts |

| Other/unknown | 2% | 1% | -1 ppt |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Pre guideline period covers 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 (N=487), post guideline period covers 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 (N=595). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

Furthermore, as with harassment, the trend of an increase in the proportion of COs and decrease in SSOs starts before the guideline comes into force and is maintained beyond the post guideline period (see Figure 8). Given that the offences of stalking and harassment are sentenced using a combined guideline it is not surprising to see a similar pattern of changes in outcomes post guideline.

However, Tables 3 and 8 show both pre guideline and post guideline, stalking is sentenced more severely than harassment. While offenders sentenced for stalking and harassment received similar proportions of COs, a higher proportion of offenders sentenced for stalking received SSOs and immediate custody, while for offenders sentenced for harassment a higher proportion received fines and discharges.

Figure 8: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by sentence outcome, by year, 2013 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Time series excludes the year 2012, due to only 2 offenders being sentenced.

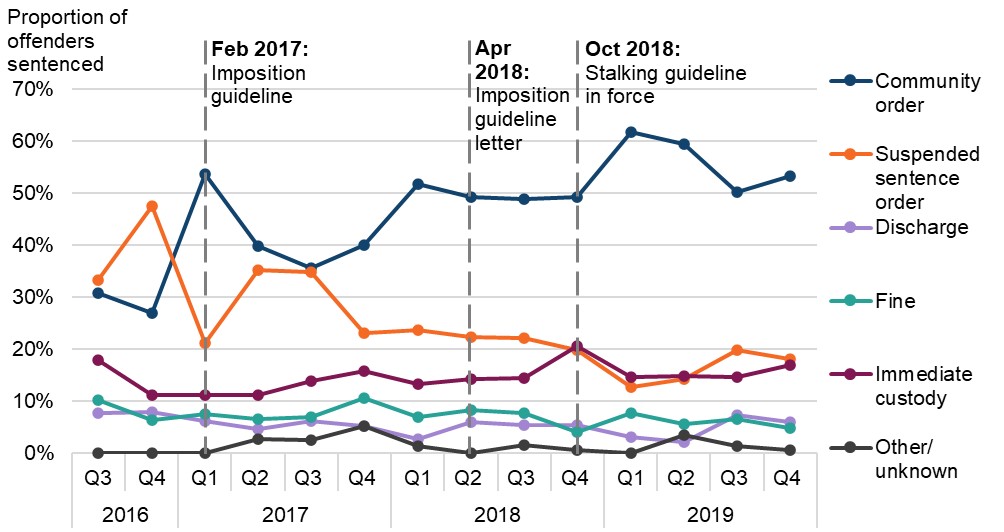

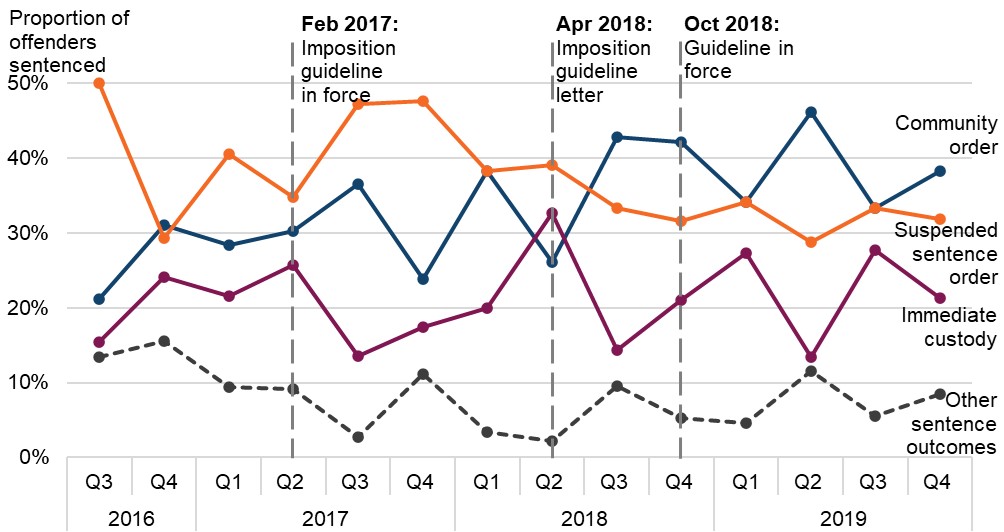

Outcomes for stalking were examined at a more granular level to see whether, as with harassment, the increase in COs and reduction in SSOs may have been influenced by the introduction of the Imposition guideline, or subsequent communication to reinforce it. The data in Figure 9 is grouped by quarter to provide a more robust comparison between time periods, due to the low volume of offenders sentenced each month for stalking.

In quarter 1 (Q1) 2017 – when the Imposition guideline was published – an increase in COs and decrease an SSOs can be seen, although this fluctuates in the following quarters. There then appears to be no clear evidence of an impact related to the publication of the Imposition guideline letter in April 2018 for stalking, as the proportion of SSOs and COs issued remain stable across Q2 and Q3 2018. Instead, an increase in proportion of COs and decrease in SSOs are seen following the Harassment and stalking guideline coming into force in October 2018 (Q4 2018) before generally stabilising by the end of 2019.

Overall, while changes were seen following the Harassment and stalking guideline coming into force, it is unclear whether this was part of a continuation of an existing trend seen from Q3 2016 onwards. Therefore, it is not possible to determine from this CPD analysis, whether the guideline contributed to the increase in proportion of COs and decrease in proportion of SSOs, or whether the changes seen were likely due to the Imposition guideline or another other factor.

Figure 9: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by sentence outcome, by quarter, July 2016 to December 2019

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Quarter 1 (Q1) covers January to March, Q2 covers April to June, Q3 covers July to September, and Q4 covers October to December.

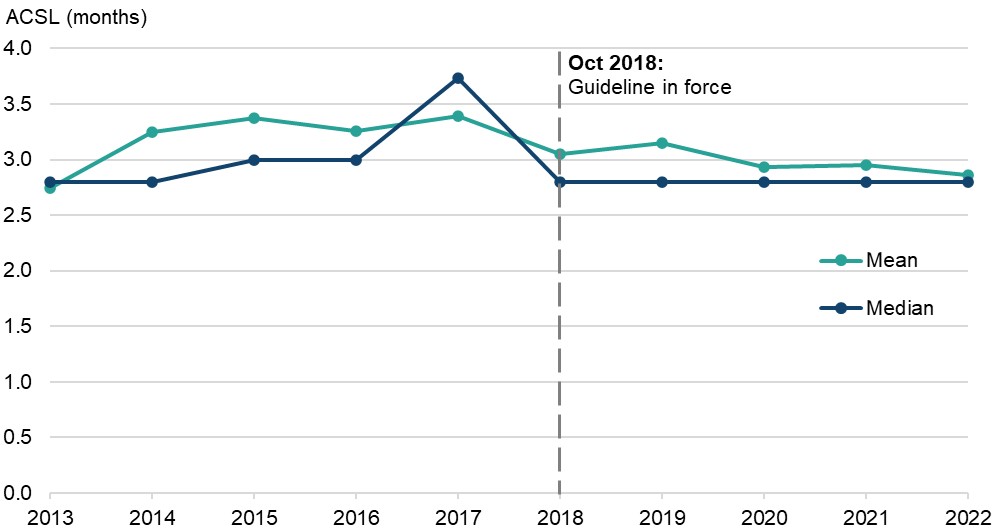

Sentence lengths

In addition to sentencing outcomes being considered, changes to sentence lengths issued for immediate custodial sentences are shown in Figure 10. The data suggests that the ACSLs between 2013 and 2022 remained relatively stable, other than a small increase in median ACSL in 2017 which immediately dropped again in 2018. There has been a very slight decrease in ACSL over time, but it is not clear whether this is guideline related, as the decrease appears to be part of a longer term trend, rather than focused around 2018 and 2019, when we would expect the biggest impact to be apparent if it was tied to the guideline.

Figure 10: Average custodial sentence length (ACSL) in months received by adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by year, 2013 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Records over the statutory maximum sentence of 6 months were excluded from analysis. Data is presented from 2013 as no offenders were sentenced to immediate custody for stalking in 2012.

3.2.4 Magistrates’ court data collection analysis

The data collection for stalking returned a relatively low response rate and as the number of records collected pre guideline is fewer than 30, caution needs to be taken when interpreting these figures. As a result of the low volumes, in depth analysis of the data has not been possible.

Table 9 shows the proportion of sentence outcomes pre and post guideline from the data collection for offenders sentenced for stalking. This broadly reflects the sentencing changes seen in the CPD, of an increase in COs and a decrease in SSOs, although in the CPD data (Table 8) the increase in COs post guideline is more prominent (a 10 percentage point increase, rather than 5).

Table 9: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by sentence outcome, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable.

| Sentence outcome | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 4% | 2% | -2 ppts |

| Fine | 4% | 7% | 3 ppts |

| Community order | 44% | 49% | 5 ppts |

| Suspended sentence order | 26% | 18% | -8 ppts |

| Immediate custody | 22% | 25% | 2 ppts |

| Other/unknown | 0% | 0% | 0 ppts |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

Pre guideline period covers 1 November 2017 to 30 March 2018 (n=27), post guideline period covers 23 April 2019 to 30 September 2019 (n=61). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

Table 10 examines the proportion of offenders sentenced for stalking by the starting point received. Unlike harassment, a much higher proportion of offenders received a CO starting point post guideline than pre guideline; however, the pre guideline proportions are based on a low sample, so care should be taken when interpreting the figures.

Table 10: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking, by starting point, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable.

| Starting point | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 0% | 2% | 2 ppts |

| Fine | 4% | 2% | -2 ppts |

| Community order | 48% | 61% | 13 ppts |

| Custody | 41% | 34% | -6 ppts |

| Other/unknown | 7% | 2% | -6 ppts |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Magistrates’ court data collection from the Sentencing Council

Pre guideline period covers 1 November 2017 to 30 March 2018 (n=27), post guideline period covers 23 April 2019 to 30 September 2019 (n=61). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

The increase in offenders receiving a CO outcome (Table 9) may therefore be due to more cases receiving a COs as a starting point (Table 10); this may be tied to the increase in CO starting points in the Harassment and stalking guideline (seven out of nine starting points) compared with the MCSG for harassment (one out of three starting points).

Overall, while the data are not robust enough to draw firm conclusions, this suggests the guideline may have led to some of the changes observed in sentencing practice. No analysis to examine the decrease in SSOs has been possible with the data collection data, due to low volumes.

3.3 Harassment (putting people in fear of violence)

3.3.1 Summary of findings

- For the offence of harassment (putting people in fear of violence) there was an overall increase in the proportion of COs, and a decrease in the proportion of SSOs issued from 2018. However, the proportions of sentence outcomes in 2022 reverted back to a similar distribution seen pre guideline.

- The changes to the proportion of COs and SSOs appear to have started when the Imposition guideline letter was published in April 2018, before the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline came into force.

- Proportions of immediate custodial sentences remained similar pre and post guideline. However, there was a slow and steady increase in ACSL until 2022, which suggests the increase was not tied to the introduction of the guideline. It was also concluded that it was not related to the increase to the statutory maximum sentence which increased from 5 years’ custody to 10 years’ custody on 3 April 2017, as any changes relating to these would have been expected to be seen in 2018 and 2019, before levelling off.

- It therefore appears that the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline has not had a clear impact on sentencing outcomes or increasing sentence lengths for immediate custodial sentences, which is in line with the intention stated in the resource assessment.

3.3.2 Background

The offence of harassment (putting people in fear of violence) is contrary to section 4 of the Protection from Harassment Act. For brevity, the offence will be referred to as harassment (fear of violence) hereafter. This offence had a statutory maximum sentence of 5 years’ custody until 2 April 2017, and from 3 April 2017 this increased to 10 years’ custody. To account for this the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline included a new ‘very high culpability’ level. The only opportunity for sentencers to arrive at a sentence greater than 5 years’ custody is contained within one box, ‘A1’, which has a starting point of 5 years’ custody.

Prior to the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline coming into force on 1 October 2018, there was a MCSG for harassment (fear of violence) which had been in force from 4 August 2008. However, this was only applicable for cases sentenced at the magistrates’ courts.

For the offence of harassment (fear of violence) the resource assessment stated that no impact was expected as a result of the introduction of the guideline, as sentencing levels were set with current sentencing practice in mind. As the statutory maximum sentence for this offence increased from 5 to 10 years’ custody as of 3 April 2017, the resource assessment suggested a small number of offenders falling into the highest category of seriousness may receive higher sentences. However, this would be attributable to the legislative change, rather than the guideline.

3.3.3 Trend analysis

Sentence volumes

Since 2012, the number of offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence) have fluctuated; however over the past 5 years, it has remained at approximately 500 to 600 each year (Figure 11).

The proportion of offenders sentenced in the magistrates’ courts and Crown Court each year are broadly evenly split. There appear to be no changes in the proportion of offenders sentenced at the magistrates’ courts relating to the introduction of the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline.

Figure 11: Number of adult offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence), by court type, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Sentence outcomes

Analysis comparing sentence outcomes indicates that the proportion of offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence) who received a CO increased by 6 percentage points post guideline, while the proportion of those who received a SSO decreased by 8 percentage points (Table 11). This follows a similar pattern in changes to sentencing practice post guideline as has been seen with harassment and stalking. The use of other sentence outcomes remained relatively stable over this period, including immediate custodial sentences which are the most common sentence outcome for this offence (around 38 per cent both pre and post guideline).

Table 11: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence), by sentence outcome, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable, k3 = less than -0.5 percentage point difference.

| Sentence outcome | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | 1% | 2% | 1 ppt |

| Fine | 1% | 2% | 2 ppts |

| Community order | 22% | 28% | 6 ppts |

| Suspended sentence order | 37% | 29% | -8 ppts |

| Immediate custody | 38% | 38% | -1 ppt |

| Other/unknown | 1% | 1% | [k3] |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Pre guideline period covers 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 (N=694), post guideline period covers 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 (N=543). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

However, when examining the sentence outcomes across 2012 to 2022 (Figure 12), the changes following the period immediately after the guideline was introduced were not maintained over time. For example, while post guideline, COs increased to around 28 per cent (Table 11), by 2022, around 22 per cent of offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence) received a CO, which is more in line with figures seen pre guideline in 2017 (Figure 12). Furthermore, the decrease seen in SSOs to around 29 per cent of offenders sentenced post guideline, returned to 36 per cent in 2022, which is again back in line with figures seen before the guideline came into force.

It would not be expected that the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline would only have had a short-term impact. This therefore suggests that either a different factor led to the changes seen in 2018 to 2020 instead of the guideline, or alternatively the guideline did have an impact in 2018, but a separate factor reversed these changes across 2021 and 2022.

Figure 12: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence), by sentence outcome, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

As with the offences of harassment and stalking, it is possible that the Imposition guideline or associated letter to sentencers played a role in affecting sentencing outcomes. Figure 13 shows the sentence outcomes for harassment (fear of violence) split by quarter rather than month, due to low monthly volumes.

Figure 13: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence), by outcome, by quarter, July 2016 to December 2019

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Quarter 1 (Q1) covers January to March, Q2 covers April to June, Q3 covers July to September, and Q4 covers October to December.

As can be seen in Figure 13, the proportion of SSOs issued started to decrease in Q2 2018 which aligns with the time the letter was sent regarding the Imposition guideline, and this decrease continued until the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline came into force in Q4 2018. The proportion of SSOs stayed broadly at a lower level than was seen before the publication of the Imposition guideline letter. The picture is the reverse for COs, which clearly increased in Q2 2018, when the Imposition guideline letter was published; this level was then broadly maintained over the period that the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline came into force.

This suggests that the publication of the Imposition letter may have had the greater impact on sentence outcomes, and the introduction of the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline may have had very little effect on the CO outcomes, and possibly a limited effect on the proportion of SSOs.

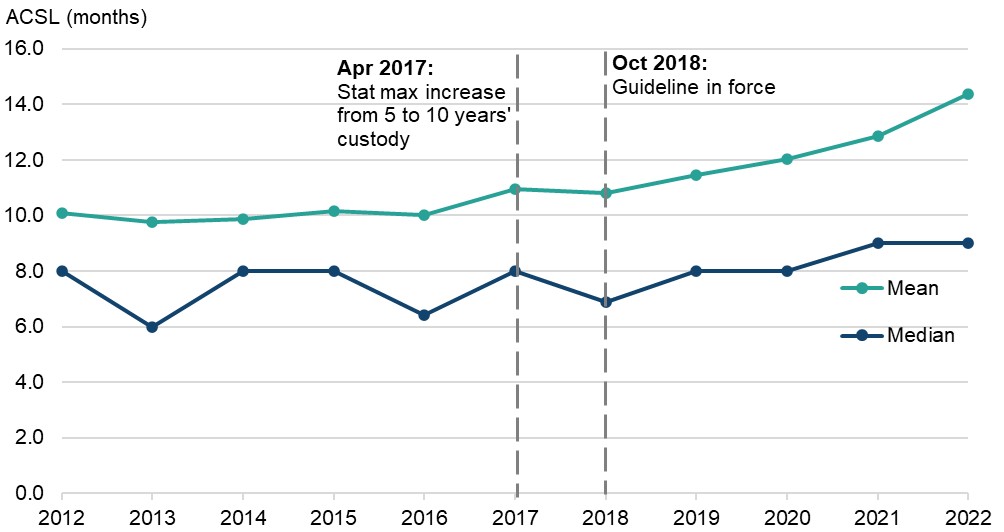

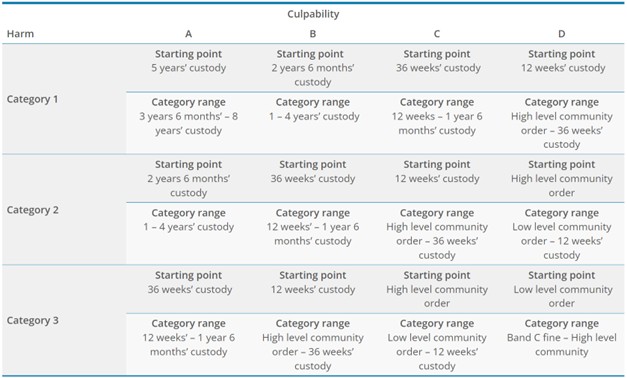

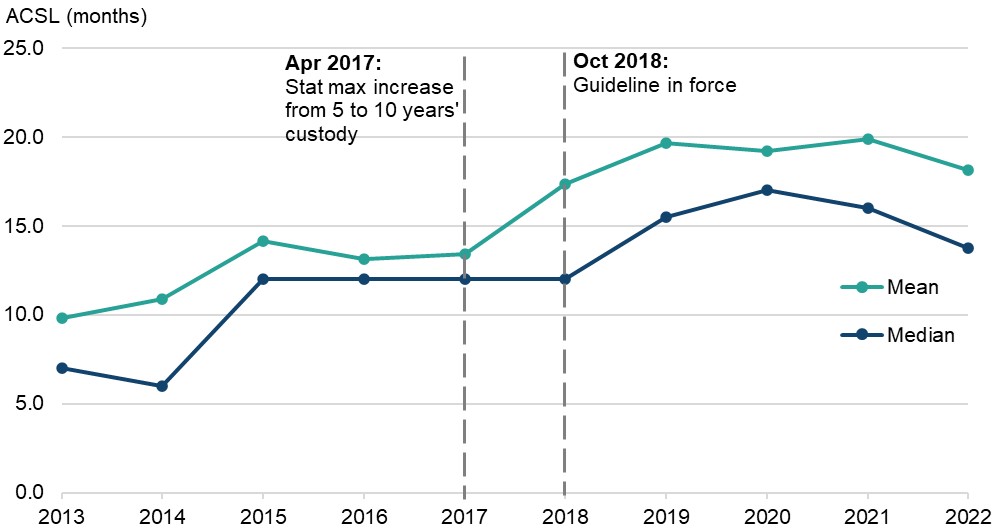

Sentence lengths

As the statutory maximum sentence for this offence increased from 5 years’ custody to 10 years’ custody from 3 April 2017, the ACSL was likely to increase as a result. Any changes to the ACSL were expected to result from the legislative change, rather than as a result of the guideline.

As seen in Figure 14, the mean ACSL increased slightly from 2016 to 2017, when this legislative change came into force, from approximately 10 months to 11 months, and a very gradual upward trend has continued since. In 2022, the mean ACSL was approximately 14 months, an increase of 4 months compared with 2016 before the statutory maximum sentence increase was in force. There is no evidence of a notable shift when the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline came into force in 2018, but an increase is seen in 2019 which could be tied to the guideline. However, the ACSL continues to gradually increase through to 2022, suggesting changes may be related to something other than the guideline. If there was an impact of the guideline alone, changes would be expected to be seen in 2018 and 2019 before remaining stable thereafter.

Figure 14: Average custodial sentence length (ACSL) in months received by adult offenders sentenced for harassment (fear of violence), by year, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

One offender in 2012 was excluded, as they received an indeterminate sentence.

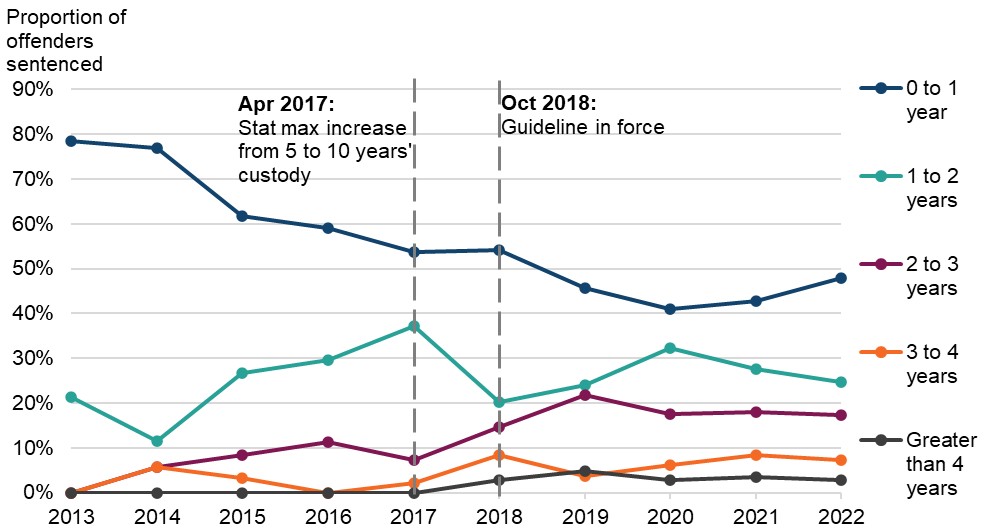

Figure 15 examines the proportion of offenders given immediate custodial sentences by sentence length for the offence of harassment (fear of violence). It is important to note that due to the time between an offence being committed and sentenced, offences committed before the statutory maximum sentence change in April 2017 would still likely be in the system to be sentenced in the months following April, and these would have been sentenced under the previous statutory maximum sentence of 5 years’ custody. Only cases which were both committed on or after 3 April 2017 and were sentenced before 31 December 2017 would be sentenced under the 10 years’ custody statutory maximum sentence in 2017. Data from the Criminal Court Statistics Quarterly October to December 2023 end-to-end timeliness tool indicates that in 2017 the average number of days (median) from offence to completion for offenders dealt with in criminal cases at the Crown Court was 234 days (approximately 8 months). The effects of this statutory maximum sentence change likely therefore continue into 2018, where an increasing proportion of harassment (fear of violence) cases would have been processed under the new statutory maximum sentence. This makes it difficult to determine whether any changes seen in 2018 would be due to the continuing effects of the statutory maximum sentence change, or also due to an impact resulting from the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline coming into force.

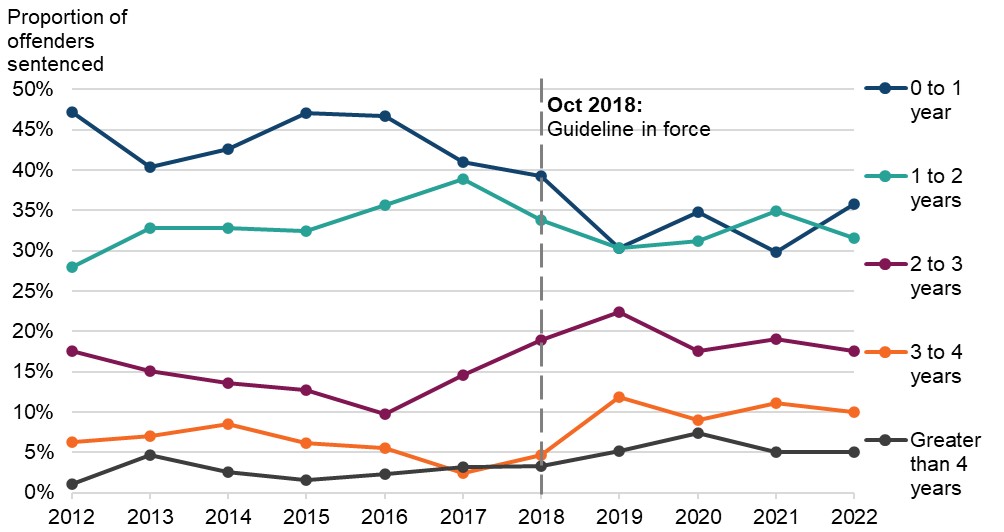

Figure 15: Proportion of offenders sentenced to immediate custody for harassment (fear of violence), by sentence length, by year, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

One offender in 2012 was excluded, as they received an indeterminate sentence.

Comparing 2017 (when the statutory maximum sentence increased from 5 to 10 years’ custody) with the year prior, sentences of up to and including 1 year decreased slightly by 6 percentage points, and there was a corresponding increase in sentences of 1 to 2 years (3 percentage points) and 2 to 3 years (3 percentage points). However, offenders receiving sentences of 3 years or more remained broadly stable.

In later years, from 2018 and beyond, the proportion of offenders receiving 2 or more years increased. These changes were particularly clear in 2021 and 2022 when offenders were receiving custodial sentences longer than 5 years for the first time. However, it is unclear what may have led to the increase in sentencing severity, as it may be expected that any changes resulting from the statutory maximum sentence change and introduction of the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline would be seen in 2017 to 2018 and then remain consistent in the proceeding years.

3.3.4 Guideline review

To understand what changes, if any, were driven by the Harassment and stalking guideline coming into force on 1 October 2018, differences between this guideline and the previous MCSG guideline were examined.

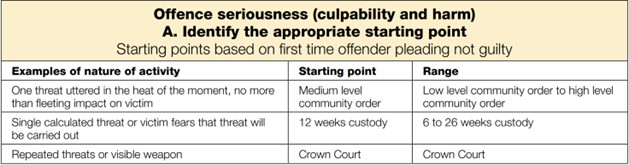

The MCSG guideline had a three-box sentencing grid, with the starting points at: 6 weeks’ custody; 18 weeks’ custody; and any cases reaching the most serious nature of activity would be sent to the Crown Court (Figure 16).

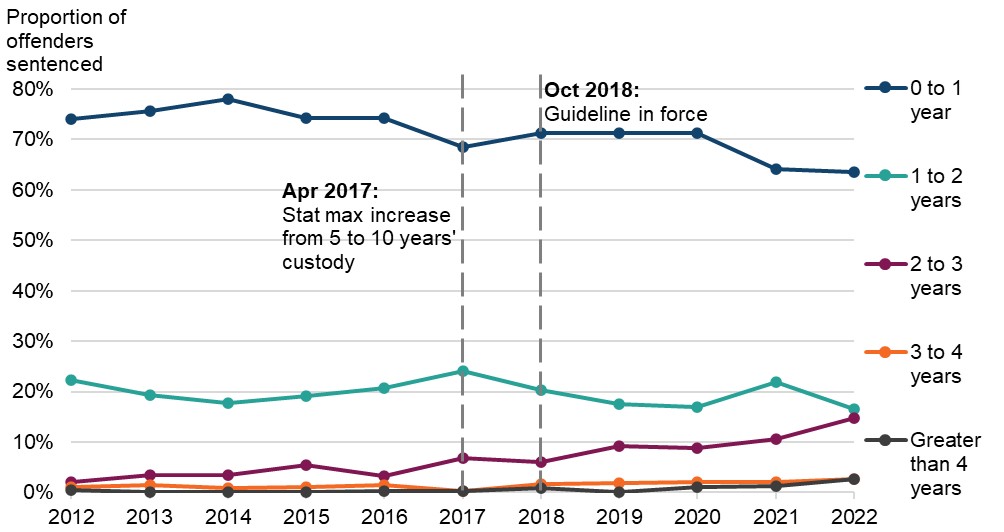

Figure 16: The sentencing table from the MCSG for harassment (fear of violence)

Source: Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guidelines from the National Archive

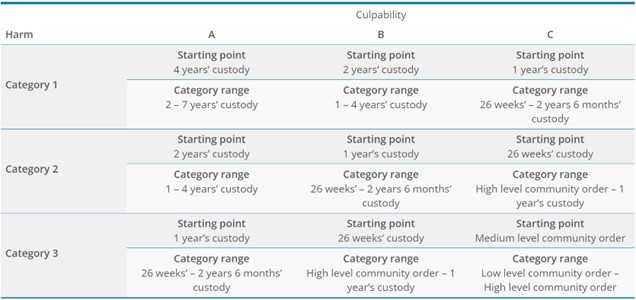

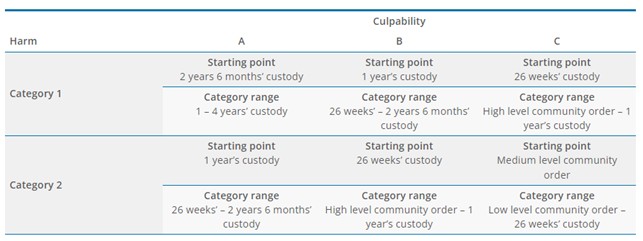

In contrast, the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline has a 12-box sentencing grid with four levels of culpability and three levels of harm (Figure 17). Of the starting points, 75 per cent are custodial (nine out of 12), and the remaining 25 per cent (three out of 12) are COs. The table ranges from a band C fine to 8 years’ custody.

Figure 17: The sentencing table from the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline

Source: Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline from the Sentencing Council website

In the pre guideline period, as shown in Table 11, approximately 22 per cent of offenders pre guideline received COs. The MCSG sentencing table included COs only in the bottom range of the lowest ‘seriousness’ category and contained no CO starting points. The increased availability of CO starting points in the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline sentencing table does not appear to have led to the increase in the proportion of COs being issued as final sentence outcomes (28 per cent in the post guideline period). Instead, Figure 13 shows that the increase in COs final sentence outcomes may be related to the publication of the Imposition letter instead.

3.3.5 Transcript analysis

A small sample of 14 Crown Court transcripts from 2019 and 2020 were examined to explore whether there were any implementation issues with the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline. The transcripts were not representative of all offending, but instead were specifically sampled to include cases receiving the highest immediate custodial sentence lengths. The cases receiving the highest sentences were of particular interest given how few cases have received a sentence of 5 years’ custody or higher, despite the statutory maximum sentence doubling from 5 to 10 years’ custody. These cases have been examined to review whether the guideline is working as intended, in particular whether the ‘A – Very high culpability’ category is capturing the expected cases.

Of the 14 transcripts included, nine cases were those receiving the longest custodial outcomes for 2020. A review of these cases showed that the majority of these (five out of nine) fell into the ‘A1’ category, the highest culpability and harm categories (determined either by what was stated by the sentencer or inferred based on the starting point, if not explicitly stated by the sentencer). The remaining four cases fell into ‘A2’ and ‘B1’ categories. Based on the factors and information stated by the sentencer, there was no evidence to suggest that these cases were miscategorised during sentencing. This suggests the reason sentence lengths have not increased more (Figure 15), or that there have not been sentences for this offence over 5 years’ custody, is not due to the guideline criteria preventing cases from falling into category ‘A1’.

Within the five cases falling into ‘A1’, the starting point was usually 5 years’ custody as stated in the guideline. Following any aggravation and mitigation, and application of any guilty plea reduction, all cases resulted in a final sentence of under 5 years’ custody. This indicates that for a case to end up with a sentence of over 5 years, it would have to be sentenced after a trial (no guilty plea reduction) in combination with aggravation being applied. For example, theoretically, even if a case increased from the starting point of 5 years’ custody to the top of the sentencing range of 8 years’ custody, after applying a guilty plea reduction of 33 per cent, the case would only just end up with a final sentence of over 5 years.

Additionally, two successful court of appeal transcripts from 2022 were reviewed for this offence, but neither transcript suggested any issues in use of the guideline.

3.4 Stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress)

3.4.1 Summary of findings

- There has been an increase in immediate custodial sentences and a decrease in the proportion of SSOs issued post guideline for the offence of stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm). However, these changes may be related to the introduction of the Imposition guideline in February 2017, rather than the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline, as no changes were seen immediately after it came into force.

- The ACSL increased in 2018 and 2019 and then stabilised across 2020 to 2022. This increase may be related to the slight increases in the proportion of cases seen before the Crown Court and the increase in offenders receiving custodial sentences of greater than 1 year.

- There has been an increase in sentence lengths across the board, rather than just at the very top end as anticipated in the resource assessment. However, it is not possible to determine how much of this impact is due to the guideline versus the change in statutory maximum sentence, which increased from 5 years’ custody to 10 years’ custody from 3 April 2017.

3.4.2 Background

Stalking (involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress) was enacted as an offence on 25 November 2012, contrary to section 4A of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 following an amendment by the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012. This offence will be referred to as stalking (fear of violence) hereafter. As with harassment (fear of violence), this offence had a statutory maximum sentence of 5 years’ custody until 2 April 2017, after which it increased to 10 years’ custody.

Prior to the introduction of the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline, no guidelines were available for use by sentencers for stalking (fear of violence).

The intimidatory offences resource assessment anticipated that the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline covering the offence of stalking (fear of violence) would have no impact on average sentencing severity for most cases. The guideline was intended to maintain similar sentencing practice. Nevertheless, it was also expected that a small number of offenders falling into the highest culpability and harm box would receive a higher sentence, to reflect the increase in statutory maximum sentence.

3.4.3 Trend analysis

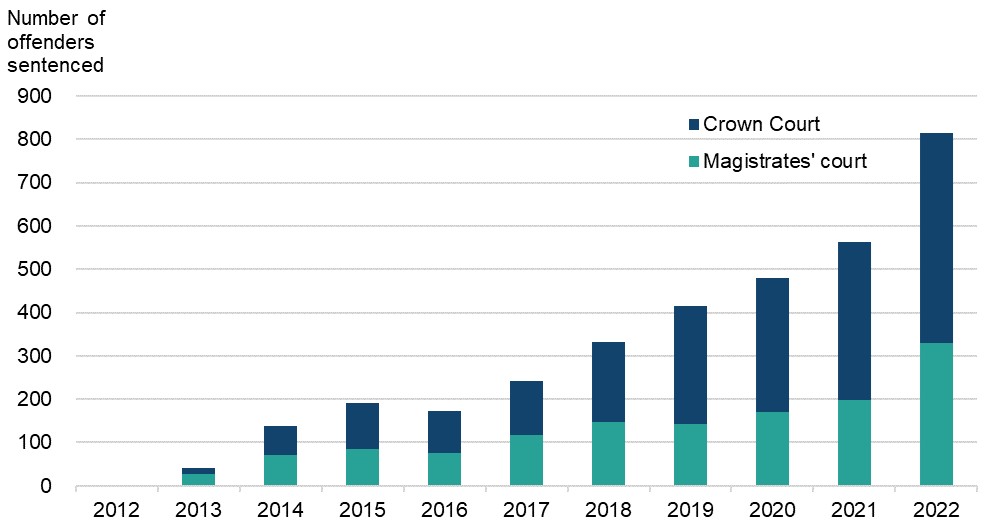

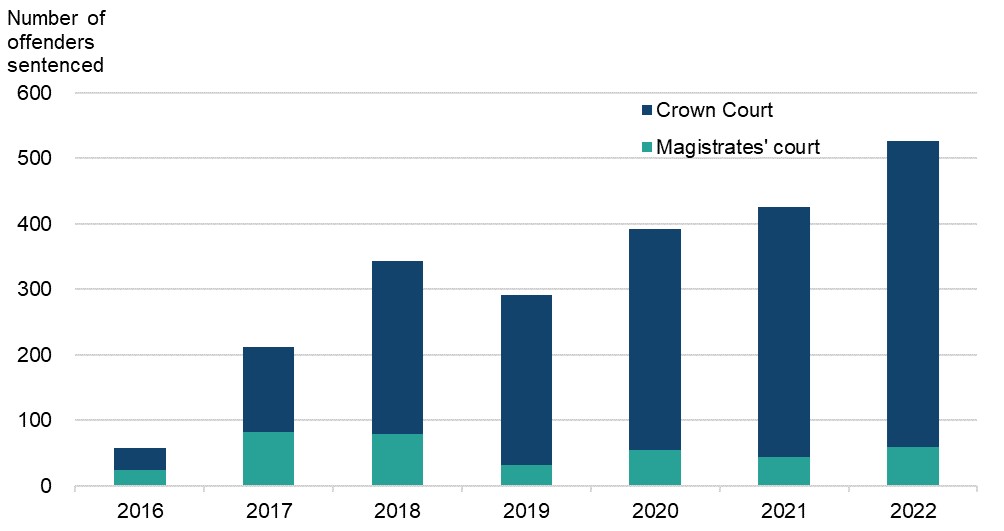

Sentence volumes

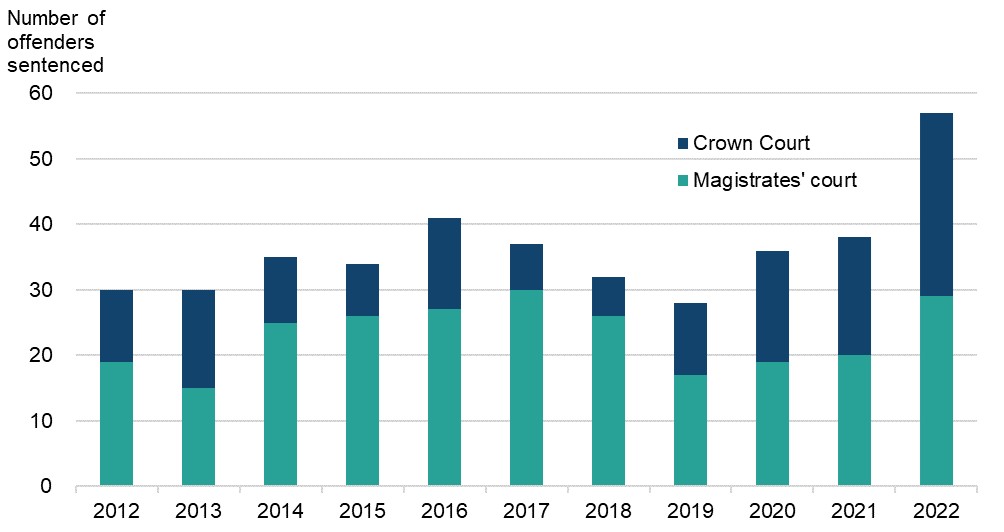

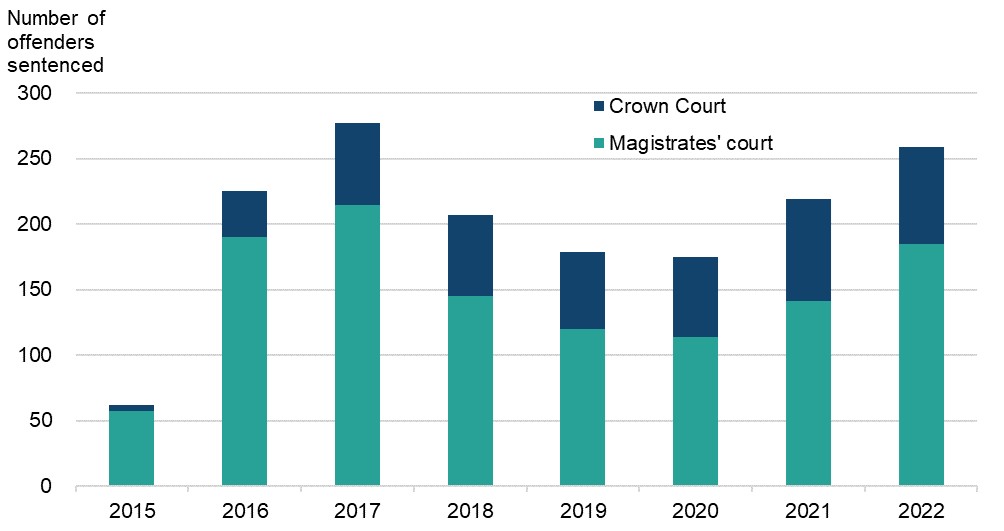

Following the introduction of stalking (fear of violence) in 2012 as an offence, volumes of offenders sentenced for this offence have generally increased year on year, including across the period the guideline came into force. In 2022, around 810 offenders were sentenced, an increase of around 250 offenders from the previous year.

The proportion of offenders sentenced in the Crown Court ranged from 50 to 56 per cent across 2014 to 2018. This then increased from 2019 onwards to between 60 to 66 per cent.

Figure 18: Number of adult offenders sentenced for stalking (fear of violence), by court type, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Sentence outcomes

When examining trends pre and post guideline, Table 12 indicates no meaningful changes in the proportion of sentence outcomes.

Table 12: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking (fear of violence), by sentence outcome, pre and post guideline

Some shorthand may be used in this table: z = not applicable, k1 = less than 0.5 per cent, k2 = less than 0.5 percentage point difference, k3 = less than -0.5 percentage point difference.

| Sentence outcome | Pre guideline | Post guideline | Percentage point (ppt) difference |

| Absolute or conditional discharge | [k1] | [k1] | [k3] |

| Fine | 1% | 1% | [k2] |

| Community order | 17% | 18% | [k2] |

| Suspended sentence order | 36% | 35% | -1 ppt |

| Immediate custody | 45% | 45% | [k2] |

| Other/unknown | 1% | 1% | [k3] |

| Total | 100% | 100% | [z] |

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Pre guideline period covers 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 (N=284), post guideline period covers 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 (N=384). Percentage totals and percentage point differences may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

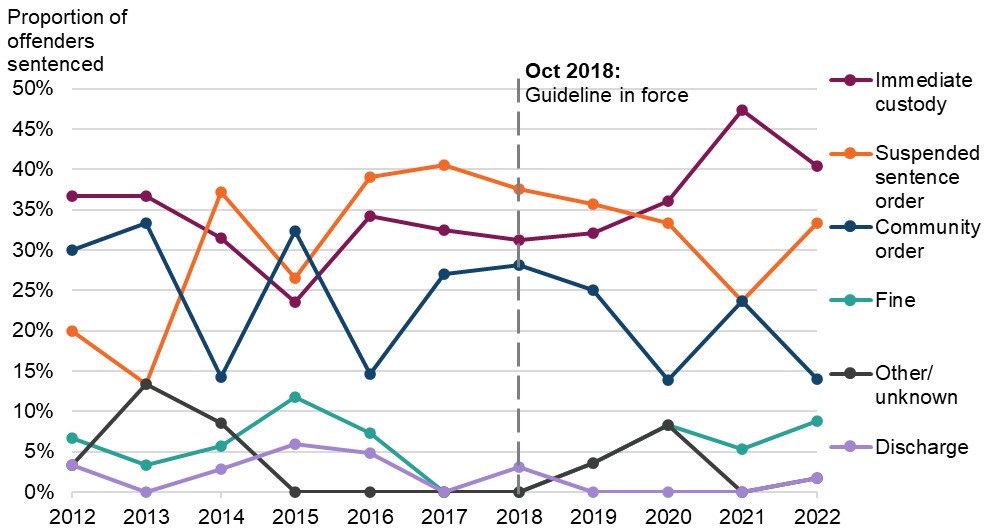

While the pre and post guideline comparisons in Table 12 show no real change in the proportions of SSOs and immediate custody, Figure 19 shows an overall decrease in SSOs between 2015 to 2020, with a large decrease in SSOs from 2017 to 2018, which then remains broadly stable until 2020. However, in 2021 and 2022, the proportion of SSOs increases again to levels seen before the introduction of the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline. The longer term trend also appears to suggest an increase in immediate custodial sentences between 2013 and 2022. In addition, although Table 12 indicates a very slight increase pre and post guideline in COs, the overall trend was one of slight decreases between 2013 and 2022.

Figure 19: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking (fear of violence) by outcome, by year, 2013 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

The time series excludes 2012, as no offenders were sentenced for stalking (fear of violence).

As with the previous offences, the change in sentence outcomes seen in Figure 19 has been examined at a quarterly level to review precisely when changes occurred and whether these align with the introduction of the guideline. It is important to note that in Figure 20, the volumes of data in each quarter are relatively low, which may explain the fluctuations seen in proportions of sentence outcomes. For instance, the volumes per quarter in 2017 were around approximately 50 to 70 offenders.

Figure 20 demonstrates that the decrease seen in SSOs, from 2017 to 2018 in Figure 19, appears to have happened following the introduction of the Imposition guideline in 2017, although this trend reverses again following the publication of the Imposition guideline letter. Due to the low volumes and quarter on quarter fluctuations in the proportion of offenders receiving SSOs and immediate custodial sentences across the time period, there is no clear evidence that these trends are related to the impact of the Harassment and stalking (fear of violence) guideline coming into force.

Figure 20: Proportion of adult offenders sentenced for stalking (fear of violence), by outcome, by quarter, July 2016 to December 2019

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

Quarter 1 (Q1) covers January to March, Q2 covers April to June, Q3 covers July to September, and Q4 covers October to December.

Sentence lengths

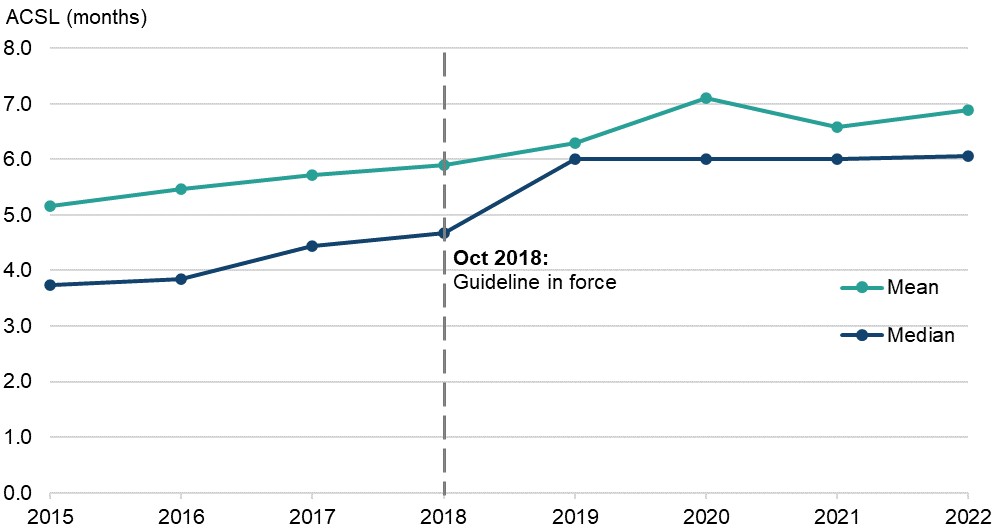

Changes seen in sentence lengths following the introduction of the guideline were also examined in Figure 21 which shows the ACSL for immediate custodial sentences for stalking (fear of violence). In 2018 a notable increase in mean ACSL can be seen compared with 2017, which further increases in 2019 before remaining broadly stable in the following years.

Figure 21: Average custodial sentence length (ACSL) in months for stalking (fear of violence), by year, 2013 to 2022

Source: Court Proceedings Database from the Ministry of Justice

The time series excludes 2012, as no offenders were sentenced for stalking (fear of violence).

It is important to note that while the statutory maximum sentence increased in April 2017, the time between an offence being committed and sentenced means that there may have been a delay in cases being sentenced under the new statutory maximum sentence showing in the data. For example, it’s possible that the finding of no substantial change in ACSL in 2017 may reflect the fact that very few cases were sentenced in 2017 which were subject to the higher statutory maximum sentence. Offences committed before the statutory maximum sentence change in April would likely still be in the system to be sentenced in the months following April and instead would have been sentenced under the previous statutory maximum sentence (5 years’ custody).