Introduction

This document fulfils the Council’s statutory duty to produce a resource assessment which considers the likely effect of its guidelines on the resources required for the provision of prison places, probation and youth justice services (s127 Coroners and Justice Act 2009).

Rationale and objectives for new guideline

The existing Imposition of community and custodial sentences overarching guideline (the ‘Imposition’ guideline) was issued on 1 February 2017 to replace the Sentencing Guidelines Council (SGC) guideline New Sentences: Criminal Justice Act 2003. The Council sought to lay out the general principles around the imposition of a community order (CO) and a custodial sentence, within the context of the sentencing decision. It also sought to clarify the factors which may make it appropriate to suspend a custodial sentence and impose a suspended sentence order (SSO), to improve the overall consistency of approach. The guideline additionally aimed to clarify any issues regarding SSOs being imposed as a more severe form of a CO, rather than for offenders whose case had properly passed the custody threshold and were eligible and suitable for their custodial sentence to be suspended.

A review of trend analysis of these sentencing outcomes in March 2023 concluded that the combination of the Imposition guideline and subsequent communications in April 2018 had been effective in directing sentencers’ attention to the guideline and clarifying the principles. This was evidenced by an increase in the proportion of COs and associated decrease in the proportion of SSOs from around April 2018. However, it acknowledged the limited scope of the research review and affirmed that the Council would be undertaking a wider policy project to examine the Imposition guideline in its entirety.

The Imposition guideline is the main guideline not only for information on when to impose a CO or a custodial sentence, including in what circumstances this can be suspended, but also for the other information it contains, such as direction on community requirements, guidance on requesting pre-sentence reports and a sentencing decision flow chart. More than six years after it was originally brought into force, changes to policy, case law and case management guidance, and further evidence about the experiences of individual offender groups in the criminal justice system, alongside a variety of both general and practitioner feedback, have led the Council to conclude that a more comprehensive review of the guideline is justified.

This review has now been carried out and the proposed revised Imposition guideline has been drafted with the intention of including fuller guidance around issues such as the circumstances in which courts should request a pre-sentence report, reference to important evidence regarding the effectiveness of immediate custodial sentences of 12 months or less and considerations courts should take into account for specific cohorts in the criminal justice system that are pertinent to the sentencing decision process. It is hoped that the new and improved guidance will continue to improve the consistency of approach and the application of principles for sentencers to impose the most appropriate sentence for each offender considering all the circumstances.

Scope

The Imposition guideline applies only to adults. This assessment therefore considers the resource impact of the draft guideline on prison and probation service resources. Any resource impacts which may fall elsewhere are therefore not included in this assessment.

Current sentencing practice

To understand the resource impact of the new guideline, an understanding of the current practice is needed. However, being an overarching guideline, there are no standard detailed offence-specific sentencing statistics to draw on as the guideline is applicable to a large number of different offences. However, it is recognised that the Imposition guideline will be most relevant to those offences for which the sentencing ranges span both community and custodial sentences and within which decisions must be made regarding which outcome is most suitable to fulfil the purposes of sentencing. Relevant figures therefore include the frequency of these outcomes, which have been produced from statistics from the Ministry of Justice’s (MoJ) Court Proceedings Database (CPD). Specific statistics from alternative sources to support understanding of the potential prison and probation resource impacts are referenced throughout the resource impact section below, at the relevant points.

Sentencing outcomes

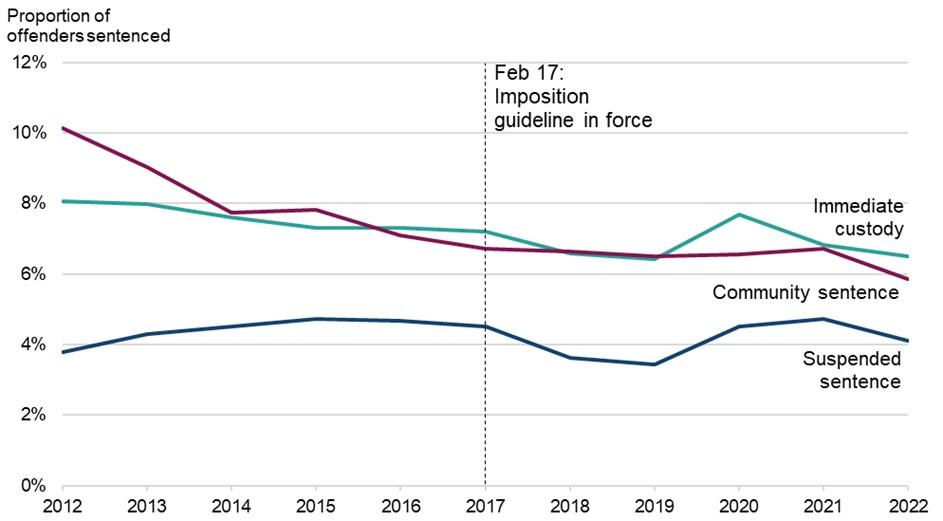

In 2022 there were around 60,600 community sentences, 42,300 suspended sentences and 67,200 immediate custodial sentences imposed for adults, comprising 6, 4 and 7 per cent respectively of total sentencing outcomes for that year. Over three quarters of all custodial sentences (both immediate and suspended) were given for triable either way offences, along with slightly under half of the 60,600 community sentences, with the remaining half almost entirely imposed for summary offences.

As seen in Figure 1, the proportion of these outcomes across all offence types has fluctuated somewhat over the last decade. While the proportion of community sentences has generally decreased, this proportion has stabilised since the current Imposition guideline has been in force, with the exception of 2022 which saw an increase in the proportion of fine outcomes driving decreases across each of these three outcomes (which was driven by increases in sentencing for motoring offences).

Figure 1: Change in proportion of community and custodial sentences out of total sentencing outcomes for adult offenders, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court proceedings database, Ministry of Justice

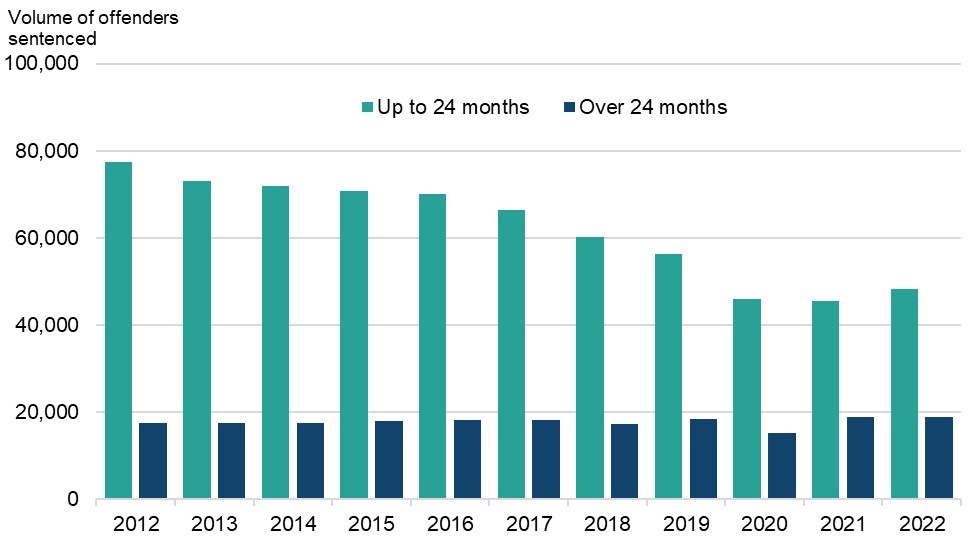

Since the Imposition guideline covers principles around when it would be appropriate to suspend a custodial sentence, it has been useful to consider current sentencing practice with regards to the volume of immediate custodial sentences being imposed above and below the 24-month threshold for which custodial sentences can be suspended.

As seen in Figure 2, the frequency of immediate custodial sentences above the 24-month threshold has stayed relatively stable over the last decade, between around 17,000 and 19,000, with the exception of 2020 when it fell to 15,200. This is assumed to be the result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic when court sitting times were drastically reduced and the imposition of immediate custodial sentences required additional considerations (see the Council’s note on the application of sentencing principles during the COVID-19 emergency).

Figure 2: Frequency of immediate custodial sentences by final sentence length, above and below the suspension threshold of two years, 2012 to 2022

Source: Court proceedings database, Ministry of Justice

Key assumptions

To estimate the resource impacts of a guideline, an assessment is required of how it will affect aggregate sentencing behaviour. This assessment is based on the objectives and anticipated consequences of the new guideline and draws upon analytical and research work undertaken during guideline development. However, some assumptions must be made, in part because it is not possible precisely to foresee how sentencers’ behaviour may be affected by the guideline itself, over and above other sources of the same information. Furthermore, for this guideline, regional differences in probation provision and evidence gaps make summarising and understanding the current system particularly challenging. Any estimates of the impact of the new guideline are therefore subject to a substantial degree of uncertainty and will be heavily reliant on an assessment of the effects of changes to the structure and wording of the revised guideline compared with the existing Imposition guideline.

The resource impact of the revised guideline is only presented in terms of changes to prison and probation resource which are expected to occur as a result of it. Any future changes unrelated to the publication of the guideline are therefore not included in the estimates.

While data exist for relevant areas such as number of offenders receiving community and custodial sentence outcomes and the frequency of pre-sentence reports, there are many areas of the revised guideline for which key baseline data are not currently publicly available, for example on volumes of deferred sentences and lengths of community requirements. It is also not possible to use a single measure to estimate probation resource as the association between caseloads and staffing depends on a variety of factors (including, but not limited to, offender risk, volume/combination of requirements and rehabilitative needs). Also, in part due to this, there are regional differences in the provision of probation-led services. As a consequence, it is difficult to estimate with any precision the impact the guideline may have, particularly on probation resources.

However, it is still important to estimate what impact the guideline may have and to consider how the guideline will work in practice. To support the development of the guideline and mitigate the risk of the guideline having any unintended impacts, some small-scale research will be conducted with sentencers during the consultation stage. It is hoped that this research provides some further understanding of the likely impact of the guideline on prison and probation resources, on which to base the final resource assessment accompanying the definitive guideline.

Resource impacts

This section should be read in conjunction with the draft guideline available on the Sentencing Council website.

Overall, it will not be possible to quantify precise impacts of the Imposition guideline due to the reasons set out above. However, it is intended that, in the vast majority of cases, the guideline should not change overall sentencing practice but instead assist sentencers to apply a broader range of principles around the imposition of community and custodial sentences in a consistent way.

The guideline has been restructured, with several changes to existing sections, as well as the addition of several new sections which are intended to have specific impacts, which are set out below. These are presented following the order in the guideline, with any available relevant supporting evidence referenced throughout.

Regarding prison resources, the guideline is not expected to have a substantial impact for the majority of offenders, although it is estimated that the direction of any change would be a decrease in required resources. For example, the new direction in the guideline on consideration of previous convictions in addition to the reference of research showing the inefficacy of short custodial sentences may result in sentencers imposing fewer short immediate custodial sentences.

In terms of probation resource, although it is expected that the guideline will lead to changes in the way that probation resources are required, particularly for certain groups of offenders, these changes cannot be quantified. For example, new direction encouraging broader consideration of the length of community and suspended sentence orders, and the imposition of different lengths/volumes of requirements and combination of requirements may result in an increase in the range of order lengths and an increase in the range of the number of requirements or their combination. Also, changes and additions to the direction regarding pre-sentence reports may result in increases in requests both for those in particular cohorts and more generally, as well as a possible increase in number of adjournments. However, this direction aligns with probation internal guidance and targets, therefore, any increase in demand and impact on probation resources is unlikely to be solely as a result of the revision of the imposition guideline.

Altogether, these changes may lead to an impact in the way that probation resources are required and will need to be coordinated (for example, between staff in sentence management teams and staff in court teams) but may not necessarily lead to an overall increase or decrease in probation resources. This is owing to the probation resource needed at court for immediate custodial sentences (when offenders are released halfway through their term on licence) and those serving sentences in the community (both suspended sentence orders and community orders.)

1. Thresholds

The thresholds section is a new section of the guideline, though much of the text within it has been taken from the current guideline. Some new wording has been added to inform sentencers that while relevant previous convictions will be an aggravating factor increasing the seriousness of the offence and can affect the intensity and length of a sentence, great caution must be exercised before they are used as the sole basis to justify the case passing the custody threshold. The new text also emphasises that numerous previous convictions might indicate an underlying problem that could be addressed more effectively through a community order.

While these two directions are new additions to the Imposition guideline, they are not new to Sentencing Council guidelines; similar direction is included in the expanded explanation for the statutory aggravating factor of previous convictions (and referenced in all offence specific guidelines).

It is intended that this section will ensure courts consider the thresholds for a community order and custodial sentence more carefully in relation to accounting for previous convictions, and not necessarily cross the custody threshold and impose a custody purely on the basis of multiple previous convictions unless absolutely necessary. It is also intended to encourage sentencers to think more flexibly about the range of different requirements that can be attached to a community order, even if an offender has already served a community order for a previous offence.

Currently, the proportion of different sentencing outcomes varies with the number of previous convictions or cautions an offender has received. According to recent statistics from the Ministry of Justice First Time Entrants into the Criminal Justice System and Offender Histories publication, adult offenders with no previous convictions or cautions sentenced in 2022 for an indictable offence were similarly as likely to receive a community sentence as an immediate custodial sentence. However, offenders with 3 or more previous convictions or cautions were more likely to receive immediate custody, and those who had received 15 or more previous convictions or cautions were over three times more likely to receive immediate custody than either a community sentence or a suspended sentence for the fresh offence.

Sentencers are likely to already be fully considering these principles in the sentencing decision, so it is not possible to estimate what impact this change to the guideline may have. However, should the inclusion of this wording substantially change how sentencers consider the weighting of previous convictions on decisions regarding whether or not the case has passed the custody threshold then (while there are many external factors that come into play) within a single offence we may expect to see some of the differences in outcome currently observed between individuals with no previous convictions and multiple previous convictions to reduce.

This should have the effect of reducing the likelihood of an offender receiving an immediate custodial sentence on the basis of multiple previous convictions alone, which would be associated with a decrease in the necessary resource required for any prison places. The impact on probation would most likely be a change in the way probation resources are required, given probation resource is needed both for custodial sentences and sentences in the community, for example, a slight increase in the demand at an earlier point for the imposition of more community sentences, rather than the delayed demand on probation after the first half of an immediate custodial sentence has been served in custody.

2. Pre-sentence reports and deferred sentences

Similar to the new Thresholds section, while there is already direction in the current guideline on pre-sentence reports (PSR), this is spread out across two different sections. The revised guideline newly brings this information together into one specific section and includes several new directions.

The section newly sets out specified cohorts for whom a PSR may be particularly important, which includes those who are at risk of a custodial sentence of 2 years or less, young adults (18-25 years) and those from an ethnic minority, cultural minority, and/or faith minority community. Furthermore, the revised guideline now sets out that where a case is being committed to the Crown Court, a PSR should be requested on committal. This is in line with a similar addition in the updated Better Case Management (BCM) Revival Handbook – January 2023.

Data are not available to understand what proportion of most of these groups currently receive a PSR under the appropriate circumstances, especially as there may be intersectionality between the groups. However, analysis undertaken for this resource assessment to compare statistics on PSRs from the biennial Ministry of Justice Equalities in the Criminal Justice System compendiums with sentencing outcomes by demographic group from the Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly: December 2022 (CJSQ) publication (excluding offenders where these demographic data were unavailable) suggests that females are already slightly more likely to have a PSR prepared before a community or custodial sentence than males are. It also indicates that offenders from an ethnic minority background are slightly less likely than white offenders to have a PSR prepared before receiving these outcomes, although the rate of unknown ethnicity is much higher in the Court Proceedings Database (CPD) source of the CJSQ publication than the probation data used in the Ethnicity and the criminal justice system statistics 2020 publication, so caution must be exercised comparing across these two data sources. Furthermore, this analysis combines two different sources with slightly different counting bases so these findings should be taken as indicative rather than conclusive.

Nevertheless, across all of the specified cohorts it is anticipated that there may be some increase in requests for the preparation of PSRs under the revised Imposition guideline, which is anticipated to require some increased probation resource, primarily for probation court staff. However, these groups of focus for which increases might be observed are aligned with probation internal guidance for staff on cohorts for whom a PSR should be requested. Therefore, any increase in resource is unlikely to be as a result of the Imposition guideline alone.

The other key change in the PSR section concerns the approach to adjournments in cases. In the revised guideline, sentencers are encouraged to liaise with Probation on whether a quality report can be delivered on the day and to adjourn the case if it cannot. Research published by MoJ on the impact and effectiveness of PSR reports for offenders (Gray et al. 2023) found that offenders who had a fast delivery oral (‘oral’) or fast delivery written (‘fast delivery’ or ‘short format’) PSR prepared for them before sentence in 2016 were statistically more likely to complete their community order or suspended sentence order (with requirements) in the years that followed than those who did not. This highlights the importance of a PSR in improving the effectiveness of sentencing outcomes.

As a result of this amended direction, it is thought there may be increases in the proportion of fast delivery/short format PSRs. These type of PSRs can be completed on the day of sentence by probation court officers, but more commonly require an adjournment, and will only be suitable where the case is not of high seriousness. In 2022 there were 83,200 PSRs prepared by the Probation Service, of which the majority (70 per cent) were prepared in the magistrates’ courts (from MoJ’s Offender Management Statistics quarterly publication)(OMSQ). Across both courts, fast delivery/short format reports were the most common type prepared, as expected, comprising around two thirds of those in the magistrates’ courts and a higher 82 per cent of Crown Court PSRs.

The other types of PSR include oral reports, which are usually completed by probation court staff on the day they are requested by the court and are most appropriate for offenders with no or low rehabilitative needs, and standard written (‘standard’) reports. Standard reports are the most comprehensive type of PSR, requiring substantially more resource and so are only appropriate for cases of higher seriousness. A further third of magistrates’ courts PSRs in 2022 were oral reports and only one percent were standard PSRs, whereas at the Crown Court oral reports were the least frequent type of PSR in 2022 at 7 per cent, compared with a higher 11 per cent for standard PSRs.

The indication for adjournment alone is not expected to drive any changes to the overall volume of reports. While this may result in changes in the way that probation resources are required, and any changes would not be as a result of the guideline alone, given similar direction in the BCM revival handbook., it is not anticipated to increase probation resource demands. However, it is acknowledged there may be regional differences in the impact of this direction, depending on current service provision particularly of probation staff in court.

Lastly, deferred sentences are newly referenced under this section in the revised guideline to better assist sentencers when considering deferring sentencing in suitable circumstances as set out in the guideline. As a result, there could be increased engagement with this option by sentencers. Concerns regarding data quality and the lack of recent published data mean that any changes will be difficult to measure accurately. Additionally, the implementation of the requirements imposed as part of deferred sentencing are managed differently in different regions (The Sentencing Code 2020 allows the court to appoint a supervisor that is either a probation officer or ‘any other person the court thinks appropriate who consents to the appointment’, which in some regions is a police officer,). This means, overall, understanding the impact of this addition will be difficult.

3. Purposes and effectiveness of sentencing

This entirely new section covers the five purposes of sentencing and introduces a ‘step back’ approach to encourage sentencers to consider if the sentence they have arrived at fulfils the purposes of sentencing. The revised guideline contains new content highlighting key considerations from the literature around the effectiveness of sentencing, and considerations for sentencing for two key cohorts of offenders: young adults and female offenders (including pregnant offenders). It also advises sentencers that research has shown that short custodial sentences are generally less effective at reducing reoffending than community sentences (for example, the evidence review commissioned by the Council and published in September 2022 on the Effectiveness of sentencing options on reoffending).

According to the latest HMPPS statistics, during 2022-23 there were 196 self-declared pregnant offenders in prison, and there was a total of 44 births to women in custody (in hospital or in transit to hospital). Also in 2022, young adults (between the ages of 18 and 24 inclusive) were equally as likely to get a custodial sentence over 12 months than a custodial sentence of 12 months of less (Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly publication). This has changed over time – in 2014, 37 per cent of immediate custodial sentences for young adults were over 12 months. This trend over time has also affected adult offenders of 25 and over, but the difference is not as pronounced, and this cohort are still more likely to receive a sentence up to 12 months (60 per cent of immediate custodial sentences in 2022, compared with 69 per cent in 2014).

It is hoped and anticipated that the new wording will encourage sentencers to consider rehabilitative alternatives to short custodial sentences in the appropriate circumstances. Sentencers may already be fully aware of these issues and actively considering the relevant purposes of sentencing, so there may be no impact from this section. Nevertheless, any impact would be likely to lead to a reduction in the proportion of short custodial sentences and a subsequent increase in alternative outcomes. Regarding young adult and female offenders, the additional considerations highlighted for these groups are hoped to lead to even greater impacts for these groups. These impacts would be most likely to lead to changes in the way that probation resources are required, (to support these offenders in the community rather than after being released on licence from an immediate custodial sentence), and a corresponding potential decrease in required prison resource.

4. Imposition of community orders

This pre-existing section of the guideline newly contains a short paragraph assisting sentencers in determining the length of a community order (CO). This additional guidance is intended to encourage sentencers to consider the full range of lengths a CO can be, to ensure it is the most suitable for the offender.

From the MoJ’s Offender Management Statistics quarterly publication, the average length of a CO starting in 2022 was 13 months and over two thirds of COs imposed were for exactly 12 months (with around one quarter given for over 12 months and the remaining 8 per cent given for less than 12 months).

As a result of this new direction, we may expect to see changes to the lengths of community orders, although not necessarily either longer or shorter on average overall. Instead, it is thought this may lead to greater variety in the lengths of different orders. As such, the overall impacts on probation are assumed to be limited, and this should not impact prison resources.

5. Requirements

The requirements section of the existing Imposition guideline has been substantially expanded to provide a comprehensive summary of each requirement, which includes the most up to date guidance on each, including the changes in legislation on electronic monitoring and curfew. Any changes to the implementation of electronic monitoring and curfew requirements observed after the guideline is in force would be as a result of highlighting these legislative changes which sentencers should already be aware of, rather than being an impact of the Imposition guideline directly.

For other requirements, additional information has been added for each one to ensure that the guideline is clear on the volume, length/range and factors to consider for each requirement, so that requirements imposed are the most suitable for the offender and their circumstances. In particular, for a rehabilitation activity requirement (RAR), the direction to impose ‘when the offender has rehabilitative needs that cannot be addressed by other requirements’, replacing existing text ‘Where appropriate this requirement should be made in addition to, and not in place of, other requirements’, may result in an increase of RAR days imposed, particularly those imposed without any other requirement. However, an estimate of this change cannot currently be quantified. If this is the case, an increase in probation resources would likely be required to manage these additional RAR days, though activities delivered as part of a RAR day can significantly vary in intensity, length of time required and probation resource necessary, and will depend on the individual offender.

Regarding the rest of this section, the majority of the content may already be being considered by courts, but it is nevertheless hoped that the inclusion of this direction will ensure better consistency of approach in imposing requirements across different regions, better understanding by courts of factors to take into account and any pre-sentencing checks (such as domestic abuse checks) to be made, and easier consideration of appropriate requirements or combination of requirements for a particular offender.

6. Community order levels

Within this section of the draft guideline, various revisions have been made to encourage sentencers to approach the imposition of punitive and rehabilitative requirements slightly differently than in the current guideline.

In the levels table of the revised guideline, reference to rehabilitative requirements have been removed from the individual levels and replaced with wording that emphasises that any requirements imposed for the purpose of rehabilitation should be determined by, and align with, the offender’s needs. This has the effect of significantly reducing the link between the seriousness of the offence and the rehabilitative requirements (unlike with punitive requirements). Additionally, the table no longer specifies the number of recommended requirements within each order level category (low/medium/high), and courts are newly directed to tailor community orders to the offender according to their specific circumstances.

According to the MoJ’s Offender Management Statistics publication, of the 59,300 offenders commencing a community order under the Probation Service in 2022, around two thirds had a RAR and half had an unpaid work requirement (UPW). Additionally, around one fifth of community orders commenced this year had both a RAR and UPW requirement (which was the most frequent combination of requirements).

While sentencers are currently already able to use their discretion to impose requirements in a tailored way, this new text underlines the importance of this and reminds sentencers of the ability to consider a variety of different intensities, lengths and combinations of requirements on a community order. It is, therefore, anticipated that the changes in this section may lead to greater flexibility by sentencers in the imposition of community requirements, resulting in a broader range of the number of requirements imposed and volume/length of the requirements on each order, possible fluctuation in the average number of requirements and changes to the combinations of requirements on community orders. It is also anticipated that there may be less association between the number of RAR days and the length of any punitive requirements in the future due to the new direction that ‘any requirement/s imposed for the purpose of rehabilitation should be determined by and aligned with the offender’s needs’, rather than the levels table suggesting that the number of RAR days should increase according to the level of community order, determined by the seriousness of the offences. While this might not increase or decrease overall probation resource, it may lead to a redistribution of resources within individual portfolios of work. However, if lots of offenders are considered as having high rehabilitative need, then there is a possibility that RAR days could increase overall, with consequent additional demand on probation resource.

7. Imposition of custodial sentences

In this penultimate section of the guideline, new wording has been added which draws sentencers’ attention to research suggesting that custodial sentences of up to 12 months are less effective than other disposals at reducing reoffending and can lead to negative outcomes.

The proportion of total immediate custodial sentences of up to 12 months has reduced since 2018 from a stable level of around 64 per cent to 55 per cent by 2022 (Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly publication). It is thought the guideline could lead to further reductions in the proportion of immediate custodial sentences shorter than 12 months being imposed, reducing prison resource.

The guideline also newly states that courts will usually benefit from Probation’s assessment of the offender’s circumstances in relation to the suspension of a custodial sentence. Finally, an additional factor ‘Offender does not present high risk of reoffending or harm’ has been added to the existing list of factors for suspending a custodial sentence, meaning there are now more factors indicating it may be appropriate to suspend than those indicating it may not be appropriate. While it is not yet known whether these additions may have an impact, any impact would be likely to increase the proportion of custodial sentences that are suspended, reducing prison resource. It is also likely to impact the way probation resources are required, but not necessarily increase demand.

8. Suspended sentence orders

This final section contains a reminder that suspended sentence orders (SSOs) are themselves already a punishment and a deterrent, and newly sets out that any requirements imposed on them would be more likely to be rehabilitative in purpose. As such, the guideline suggests that courts should contemplate if a CO may be more appropriate if they are considering more onerous, punitive, or extensive requirements.

The mean number of requirements on a CO commenced in 2022 was 1.6, and this figure has been stable for the last four years (Offender Management Statistics publication). On average, more requirements are currently given on SSOs, with an average of 1.8 requirements in 2022, and this figure has been increasing since 2016.

It is hard to predict what the impact of the new guideline wording might be, but we might expect a greater mean number of requirements on a community order than a suspended sentence order in the future, with no overall increase in the number of requirements being imposed. There may also be changes to the type of court order from SSO to CO if sentencers consider these to be more appropriate, although this cannot be quantified. These changes would be unlikely to impact probation resources as both of these sentences are managed by probation in the community, and they are also not expected to impact prison resources.

Risks

Risk 1: The Council’s assessment of current sentencing practice is inaccurate or incomplete

An important input into developing sentencing guidelines is an assessment of current sentencing practice. The Council uses this assessment as a basis to consider whether current sentencing levels are appropriate or whether any changes should be made. Inaccuracies in the Council’s assessment could cause unintended changes in sentencing practice when the new guideline comes into effect.

Given it has not been possible to ascertain a reliable measure of current sentencing practice for many of the elements in the revised guideline, it is not possible to understand with any certainty the impact the guideline may have on sentencing. This risk is mitigated by information that is gathered by the Council as part of the guideline development and consultation phase. This includes interviews with sentencers as part of the consultation exercise and inviting views on the guideline. However, there are limitations regarding the scenarios that can be explored relevant to Imposition because the application of the principles within the sentencing decision are so context dependent and cover such a broad range of offences, so the risk cannot be fully eliminated.

Risk 2: Sentencers do not interpret the new guideline as intended

If sentencers do not interpret the guideline as intended, this could cause a change in the average severity of sentencing, with associated resource effects. For example, the addition of wording in the draft revised Imposition guideline which references the negative outcomes of short custodial sentences under 12 months could encourage sentencers to impose longer custodial sentences, rather than to consider alternative outcomes.

The Council takes a number of precautions in issuing a new guideline to try to ensure that sentencers interpret it as intended. Research with sentencers carried out during the consultation period should also enable issues with implementation to be identified and addressed prior to the publication of the definitive guideline.

Consultees can also feed back their views of the likely effect of the guideline, and whether this differs from the effects set out in this consultation stage resource assessment. The Council also uses data from the Ministry of Justice to monitor the effects of its guidelines to ensure any divergence from its aims is identified as quickly as possible.

Further information

Figures presented include the time period from March 2020 in which restrictions were initially placed on the criminal justice system due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, and the ongoing courts’ recovery since. It is therefore possible that figures and trends may reflect the impact of the pandemic on court processes and prioritisation and the subsequent recovery, rather than a continuation of the longer-term series, so care should be taken when interpreting these figures.

Data sources and quality

Criminal Justice Statistics

The Ministry of Justice’s Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly (CJSQ) publication is one of the main data sources for the statistics in this resource assessment. Where court outcome figures are, the volumes only include cases where the specified offence was the principal offence committed. When an offender has been found guilty of two or more offences, the principal is the offence for which the heaviest penalty is imposed. Where the same disposal is imposed for two or more offences, the offence selected is the offence for which the statutory maximum penalty is the most severe. Although the offender will receive a sentence for each of the offences that they are convicted of, it is only the sentence for the principal offence that is presented here.

It is important to note that these data have been extracted from large administrative data systems generated by the courts and police forces. As a consequence, care should be taken to ensure data collection processes and their inevitable limitations are taken into account when those data are used. Further details of the processes by which MoJ validate these data can be found inside the ‘Technical Guide to Criminal Justice Statistics’ which is published with the data.

Offender Management Statistics

The Ministry of Justice’s Offender Management Statistics quarterly (OMSQ) publication is another source of statistics in this publication. Available data on volumes of pre-sentence reports, volumes and combinations of community requirements and average lengths of community orders and suspended sentences have been taken from the quarterly and annual 2022 data tables. Further information on the data sources and quality can be found in the ‘Guide to Offender Management Statistics’ alongside the publication.

First Time Entrants and Offender Histories

The Ministry of Justice’s First time entrants (FTE) into the Criminal Justice System and Offender Histories: year ending December 2022 publication has also been used in this report to look at the trends in outcome by offending history. These statistics are compiled from the Police National Computer (PNC). Further information on the data source behind this publication can be found in the ‘Guide to Offending Histories and FTE Statistics’ which is published alongside.

General conventions

Actual numbers of sentences have been rounded to the nearest 100, when more than 1,000 offenders were sentenced, and to the nearest 10 when fewer than 1,000 offenders were sentenced.

Proportions of sentencing outcomes have been rounded to the nearest integer. Percentages in this report may not appear to sum to 100 per cent, owing to rounding.